When eaten in spring, siraegi that has grown sweet after enduring the cold weather of late autumn and winter feels like a gift to the palate. This humble vegetable is an acquired taste, but once it grows on you, it’s hard to forget.

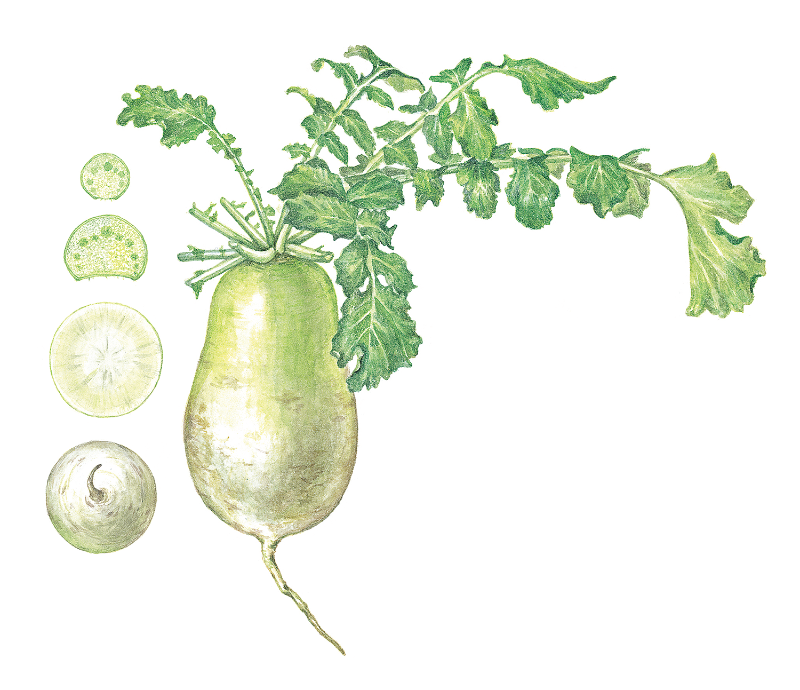

Each part of the radish has its own use and a different taste depending on the season. When radishes are harvested in winter, the green stems and leaves at the top are cut off, tied together and dried in the sunlight and wind throughout the cold months to make siraegi. These dried radish tops enrich the spring table with their savory flavor and abundant natural fiber. Siraegi needs to be repeatedly frozen and thawed at least three times before reaching it’s full flavor.

Some foods that are now prized delicacies had trivial beginnings. Such is the case with siraegi, which refers to radish stems and leaves or the outer leaves of cabbage dried in the sun and wind.

Since ancient times on the Korean Peninsula, kimchi has been made in great quantities in late autumn to eat throughout the winter. This annual custom of making, storing and sharing kimchi for winter is called kimjang and has been inscribed on UNESCO’s List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Winter kimchi is made by mixing cabbage and radish with various seasonings, such as green onions, garlic and red pepper powder, as well as salted and fermented seafood. The greens of the radish and outer leaves of the cabbage are not used.

When these leftover parts are dried fresh or boiled and then dried, they become siraegi. In the standard Korean dictionary, the outer leaves that are left over after trimming are generally called ugeoji – literally, “removed tops.” Dried radish or cabbage leaves are a sub-category of ugeoji. Although ugeoji is a word also used to describe a “frowning facial expression” due to the food’s shabby appearance, it becomes a good ingredient when carefully dried.

As Chinese cabbage or other vegetables grow, their outer leaves are exposed to rain and wind.Compared to the inner leaves, the outer leaves become rough and damaged, and therefore seem low in quality. They easily turn yellow or become limp. However, in the days when people barely managed to subsist on herb roots and tree bark, they could not afford to throw these leaves away. They picked up vegetable hulls, dried them in the shade, chopped them up and boiled them to make a porridge with a handful of rice, tofu dregs or wheat bran. During the spring lean season in particular, newspapers would report on farmers who pleaded for even just enough siraegi porridge to eat.

Chinese cabbage contains a lot of free glutamic acid, which gives it a savory taste. Radish stems and leaves contain more glutamic acid than theradish root. Sulfur compounds and glutamic acid are naturally present in meat and are responsible for the meaty flavor. Thanks to this flavor substance, siraegi goes surprisingly well with meat. Siraegi stew or soup made with red pepper paste or soybean paste and garlic has the flavor of meat without actually containing meat. Adding anchovy stock makes the broth even more flavorful. In Tongyeong, a southern port city famous for its food, siraegi soup is cooked with eel bones instead of anchovies.

AN ACQUIRED TASTE

Siraegi isn’t the kind of food you instantly get used to. The smell of boiling siraegi in the yard of a country house on a cold winter day is not especially appealing. I like the feeling of the hot steam warming the house, but I don’t like the smell, which comes from the sulfur compounds produced when cabbage or radish stems and leaves are boiled. While being boiled, however, the bitter spiciness is reduced, with the flavor turning soft and mild.

It is true that siraegi can be an acquired taste.It is said that for children to accept and like an unfamiliar food, they must taste it at least 8 to 15 times. Siraegi soup fits this deion perfectly. I don’t remember when I first tasted it, but I do remember that for a long time I didn’t care for it. Then, oddly enough, one day I started liking it. And once I fell in love with siraegi, I was able to enjoy most of the dishes made with it: siraegi seasoned with perilla, siraegi simmered in soybean paste and various seasonings, and siraegi soup made with beef bone broth, all of which are delicious.

In Korea, the 15th day of the lunar new year is a traditional holiday called daeboreum, or the “great full moon day.” In 2022, by the Gregorian calendar, this day falls on February 15. It is a day for eating mungnamul, which literally means “old greens,” and ogokbap, or rice made of five different grains. Mungnamul refers to a variety of dried vegetables and greens, such as gourds, cucumbers, mushrooms, pumpkins, turnips, bracken, aster, cucumber stems and eggplant skins. These are dried and stored during the winter to be eaten later boiled and seasoned. Siraegi also falls under this category.

Some of the most famous siraegi comes from Haean Basin in Yanggu County, Gangwon Province, located some 300-500 meters above sea level, where the daily temperature difference exceeds 20 degrees in winter. The eroded basin has also been known as the “Punchbowl” since it was so named by an American journalist during the Korean War.

© Shutterstock

Hong Seok-mo (1781-1857), a scholar of the late Joseon Dynasty, wrote in his 1849 book, Dongguk sesigi (“Record of Seasonal Customs in the Eastern Country”), that eating dried greens on the first full moon day of the year means you will not suffer from the heat in the coming summer. Although it is difficult to find a scientific basis for this statement, there is no doubt that dried vegetables are sufficiently nutritious. When vegetables are boiled and dried, chlorophyll changes in color from green to a rather dull yellow-green, but chlorophyll itself isn’t a nutrient absorbed and used by the human body. And while some water-soluble vitamins such as B vitamins and vitamin C are lost, most of the fat-soluble vitamins and minerals remain.

According to the Korean Food Composition Table published by the Rural Development Administration, 100 grams of blanched radish siraegi contains 4 grams of protein, 9.8 grams of carbohydrates, 0.3 grams of fat and 10.3 grams of dietary fiber. Just two plates of siraegi will give you more than half of the 25 grams of your daily recommended dietary fiber intake. And while siraegi eaten in mid-winter cannot be expected to show its effects in summer, for those prone to constipation, a siraegi dish served often at the spring dinner table will certainly help.

Siraegi boiled for a long time and soaked in cold water is used in various dishes. It is mixed with finely minced beef or pork and assorted seasonings then stir-fried to make a special dish enjoyed on the first full moon day of the lunar new year.

© Getty Images Korea

GIFT OF COLD WEATHER

Siraegi these days differs from that of the past. In days gone by, leftover radish stems and leaves from making kimchi were collected and dried without anything going to waste. Now, a radish variety suitable for siraegi has been developed and is grown separately. Siraegi produced from these radishes is softer in texture, which means it can be cooked without going to the trouble of peeling the stems first. Accordingly, this radish variety with more leaves is planted at wide intervals, and when the stems and leaves have grown sufficiently, they are cut to make siraegi while leaving the radishes behind. The radishes are harvested 45 to 60 days after sowing, with smaller ones sometimes left in the fields. This radish variety grown exclusively for siraegi has a slightly spicy taste and is softer than regular radish, which makes it unsuitable for kimchi. Instead, it is used to make dongchimi (white radish water kimchi) or mu jangajji (pickled radish), or is shredded, dried and roasted to make tea.

Siraegi is harvested and eaten all over Korea, but Yanggu in Gangwon Province is most famous for its production. The Haean Basin of Yanggu County, surrounded by high mountains, is called the “Punchbowl,” a name coined by an American war correspondent during the Korean War. That the English word referring to the topography of the eroded basin remains in use today means that this place was a truly ferocious battlefield. These days, however, more people associate the Yanggu Punchbowl with siraegi than with the bloody battles of seven decades ago. Siraegi produced there tastes good because of the strong sunlight, as suggested by the syllable yang in the place name, which means “sun.”

The sunlight in Yanggu is very bright and the colder weather also helps to make the radish sweet and mild. In winter, to prevent vegetables from freezing, the moisture in the leaves, stems and roots decreases and the content of sugar and sweet-tasting free amino acids increases. In the cold and less sunny fall to winter months, fewer pungent flavor substances are produced, which is why kimchi tastes better when made with winter cabbage and radish. For the same reason, although siraegi is available all year round, it tastes best when eaten in cold weather.

Siraegi can be a tasty addition to spaghetti aglio e olio or cream pasta dishes. A spoonful of perilla oil adds to the savory flavor, while the dried radish greens cut into small pieces provide a crunchy texture.

© blog.naver.com/catseyesung

TENDER TEXTURE

Once you have grown familiar with the unique taste of siraegi, you will realize that there is no food with which it doesn’t pair well. It is an ingredient in common home-cooked dishes such as parboiled greens (namul), porridge (juk), stew (jjigae) and soybean paste soup (doenjang guk), and when added to rice before cooking, it turns the staple into a delicacy. After a simple meal of siraegi rice, you’ll want to protest the recent attack on grain foods.

A food as delicious as siraegi can’t just be eaten by Koreans. Italians in Puglia also eat turnip stems and leaves stir-fried in oil with orecchiette, ear-shaped pasta. The fresh stems and leaves are also washed and ground with Parmesan cheese, garlic, olive oil and pine nuts to make radish pesto. Since the turnip greens are used raw, the pesto has a tangy taste that is softened by the addition of nuts.

Since ancient times, there must have been a universal rule to consume ingredients sparingly without throwing away anything that can be eaten. Siraegi, once considered a food for the poor, has now become a delicacy enjoyed by everyone, reborn with a softer texture and taste. It is similar to how polenta, a boiled cornmeal dish eaten by poor Italian farmers in the 16th century, came to be prized by gourmands in modern times.This shows us why we shouldn’t forget siraegi’s past while we enjoy its softer and more enhanced taste.