Made entirely by hand from start to finish, the works of metalsmith Sim Hyun-seok communicate the artist’s restrained aesthetic and warm sensitivity. Each day in Sim’s studio is as regular as clockwork, dedicated wholly to a process guided by his belief that handmade objects enrich our lives.

Sim Hyun-seok in his metalsmithing studio in Gapyeong, Gyeonggi Province. Most of his works are variations on common, everyday objects, a result of his process in which he devises solutions to his own needs and then turns the most successful of these experiments into his art.

A few years ago, Sim Hyun-seok moved his workshop and home to Gapyeong, Gyeonggi Province – a decision that reflected his longstanding desire to live a life of farming and raising flowers. Until then, he had spent most of his time in Seoul’s Hwagokdong neighborhood, working in the studio of his teacher and mentor. It was an apprenticeship that spanned some 26 years, a commitment that may be difficult to understand for today’s younger generations, who prioritize free time and self-care. After so many years of approaching each day with the mindset of a “student,” the metalsmith remains modest and straightforward even today, simply accepting the various ins and outs of a given process.

Sim’s works are all objects that people use in daily life, from fashion accessories and home goods to his signature pinhole cameras, which he made entirely by hand, down to the smallest component. After majoring in arts and crafts at Konkuk University, Sim went on to deepen his study of metalsmithing at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, earning a master’s degree. In 2015, he received the Metalwork and Jewelry Award of the Year from the Yoolizzy Craft Museum (founded in honor of Professor Yoo Lizzy, a pioneer of contemporary Korean metalwork), and has since shown his work in numerous galleries and institutions in and outside of Korea, solidifying his reputation as an artist of exceptional skill with a fascinating body of work.

Silver seems to be your go-to material. Why?

In the royal court of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), silver spoons were used to make sure that the food didn’t contain any substances that might be harmful. When certain toxins come into contact with silver, the color of the metal changes to black. This also means that silver is quite good at absorbing harmful ingredients. That’s why I keep pieces of silver in water. It maintains freshness and improves the water quality. Because silver ware is expensive, people tend to lock it away in their display cabinets, but if you do that, it will discolor. Silver that’s used every day doesn’t change color.

People also tend to think that silver is tricky to work with because it’s so soft, but that’s not exactly true. We use a lot of sterling silver in metalsmithing, which is actually 92.5 percent silver and 7.5 percent copper, making it quite hard. And more affordable, too.

What are you working on now?

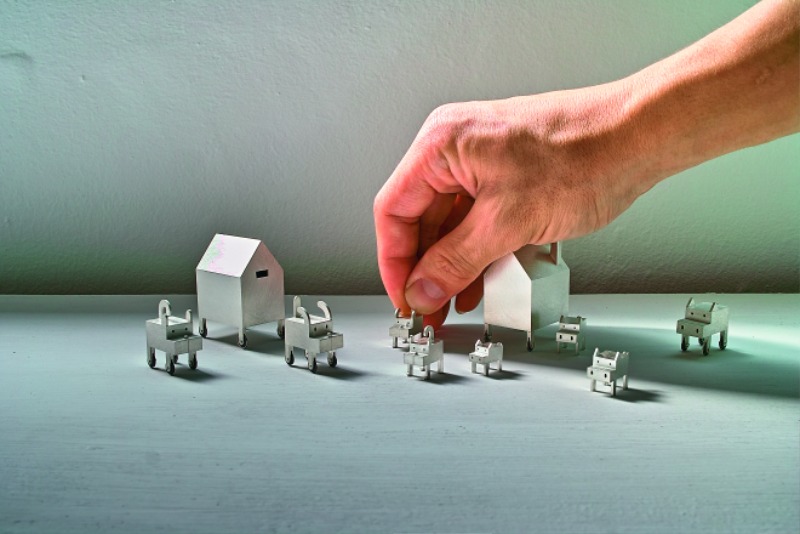

I’ve been steadily working on a line of accessories, including a dog-shaped brooch, and I continue to work on pieces that explore geometric shapes. I need the fun projects so I can keep working on the meticulous fine art pieces, too. It’s a balancing act.

Recently I’ve been making stainless steel cutlery. Stainless steel is a great material for making cutlery. It’s so much stronger than most other materials, and unlike silver, brass, or copper, it doesn’t change color. At the same time, though, it can be rather difficult to work with. It has to be welded rather than just soldered, and there are certain aspects that really require a more industrial set-up than a private workshop – so I’m currently trying to figure out whether and how I’ll be able to work with it in my usual way.

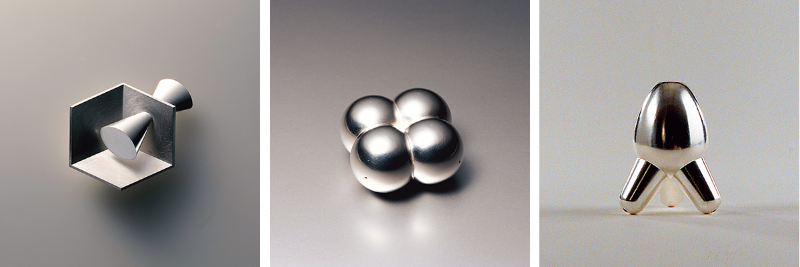

Geometric accessories. Sim usually uses sterling silver, a harder metal, and has recently started using stainless steel as well. Courtesy of Sim Hyun-seok

Cute, playful accessories. Preferring to give his practice a sense of balance, Sim takes turns between meticulous, aesthetically oriented projects and those more lighthearted and fun.

Sim’s most representative work is his fully-functioning, silver pinhole camera. Every part of the camera – from its body to every gear and component inside it – was made by hand. Just one of these cameras takes at least a few months to produce.

What is your “usual way”?

I mean where the entire process is completed with my own two hands, start to finish. I have a good understanding of what I’m actually capable of doing, and I always want to do the very best I can within the bounds of that ability. Small objects that fit right in your hand can be some of the most challenging to make, and those are the very things that I want to get better and better – and better still – at crafting.

How did you get into pinhole cameras, your signature work?

The pinhole camera is, indeed, the piece that helped raise my profile in the world at large, but it’s been quite a few years now since I last made one. Around 20 years ago, I lucked into a good deal on a Leica camera, but to take proper pictures of my pieces, I had to purchase a different lens. When I looked into it, I saw that it cost around US$900 to US$1,000. So I thought maybe I’d try making one myself. And so I did. When I used it, the pictures actually came out pretty nicely. Then I thought: I bet I could make the body of the camera, too. That’s how I ended up making a full camera with my own two hands, and the pictures I took with it could be developed properly, too, just like any camera. I’d say that pretty much sums up my creative process. I make something that I need myself in that moment, and if I’m satisfied with the result, then that’s when I begin the work of turning it into an actual piece….

Was there a special reason for your long apprenticeship?

When I was in college, I had the good fortune of meeting the artist Woo Jin-soon, by chance. He was invited to lecture at our school, and we got to know one another. There were a lot of things about him that appealed to me, from the way he worked with silver to his general aesthetic. He had pursued his studies at Konstfack in Stockholm, Sweden’s largest university for arts, crafts and design, so he could also teach me what kind of work artists were making in Northern Europe and how, which was great. I was with him from 1992 to 2018, working in his studio every single weekday from five or six in the morning to three or four in the afternoon – with a Saturday thrown in there every now and then, too. Eventually, though, he had to move out of that studio, and that’s when I ended up moving out here myself.

These days, I get started at nine in the morning and work until six in the evening. I’m always thinking about living each day as well as I can. Rather than thinking ahead to where I want to end up, I try to be more like a leaf floating along on the surface of a stream – just getting through the day, making a little headway in the direction I’m headed without sinking too far or getting stuck. I tend not to make too many plans. This aspect of my personality probably helped when it came to staying on as an apprentice for so long.

“Small objects that fit right in your hand can be some of the most challenging to make, and those are the very things that I want to get better and better – and better still – at crafting.”

A piece by Sim Hyun-seok, exhibited at the 2009 Craft Awon group show, “The Peddlers’ Travels.” Many of Sim’s most moving works are tiny, requiring intense concentration and extreme attention to detail.

Courtesy of Sim Hyun-seok

What was unique about your apprenticeship?

Well, to tell the truth, I’m a pretty careless person, and it was only over the course of learning from my teacher that people first began to tell me that I was meticulous. And in following each necessary step all the way through, I became habituated to that kind of thoroughness, and that, in turn, shaped my approach to my own practice. Take sanding, as one example: 240, 400, 600, and so on – as the fineness of the paper goes up, it makes sanding the metal that much smoother. I never skip any steps with sanding and use the sandpaper that fits each stage of the polishing process before moving on to the next. It doesn’t actually make that much difference in the end, even if you do skip a few steps, but this is just the way I’ve always done it.

If I were to give you another example, when you’re soldering two panels together, you use this compound called borax. Borax helps the soldering process and prevents oxidization. The thing is, it’s surprisingly difficult to keep the workspace clean when you’re working with those materials, so it doesn’t take long at all for the studio to become chaotic. But both Mr. Woo and I are pretty exacting when it comes to cleanliness, so we were always tidying things up and washing our hands before actually starting to work. Many people find my pieces to be very precise; I think it’s very likely that that’s a reflection of my commitment to this kind of step-by-step process.

Is there anything in particular that you’re currently looking forward to?

I just want to keep this steady pace going. I do have plans for an exhibition abroad, so I’ll have to make some preparations for that. Ah, come to think of it, I would like to try launching a “Craft Repair Shop.” Since I’m someone who works with metal, I’m actually pretty good at splinting or joining broken kitchen tools and things like that, and bringing them back to life. One of the merits of metal pieces is that they don’t shatter. Even if a metal piece gets crumpled badly, if you can apply enough pressure from the other side, it’s usually possible to recover its original shape, to a certain extent. Just like it’s possible to use a needle to sew up a torn leather sofa. Mending broken objects like that and giving them new life, making it possible for the original owner to keep on using them for a long, long time – now that’s meaningful work.