What this young Frenchman does – or what his art is about – is not easy to explain. He says he has long been interested in “making disparate elements meet” by “integrating everything related to sound and the visual arts” or “gathering those two worlds together.” And he chose Korea as his studio.

Growing up in Marseille, France, Rémi Klemensiewicz heard about Korea and its neighbors through his father, an art professor who often had exhibitions in Asia.

By the time he entered the Marseille-Mediterranean School of Art and Design (ESADMM), Klemensiewicz was leaning toward Asia and Eastern philosophy. He befriended Korean students at the school and, at the invitation of one of them, made his maiden trip to Korea in 2009, bolstered by his self-taught Korean language skills.

“That visit had a very strong effect on me. It felt like another world,” Klemensiewicz says. “I felt there were some things here that were perfectly coherent to me, and at the same time, totally different from what I was used to. And somehow those different things fit with me very well.”

In the following years, Klemensiewicz spent all his school vacations in Korea. He found it difficult to articulate his motivation, but felt the trips were the “obvious” and “natural” thing to do. While studying the language and soaking up the culture, he experienced the experimental art scene in Seoul. He also discovered that Koreans were very receptive to his art ideas.

One of his academic requirements was an internship abroad, so Klemensiewicz did a fourmonth stint at an art consulting firm in Seoul in 2011. This experience galvanized his resolve to make Korea his new home. After graduation, he told himself, “I have to go there, I have to spend time there, I want to do things there.” In 2013, he returned to stay.

Klemensiewicz is often called a sound artist or intermedia artist, but his self-deion is simply “an artist who is interested in sound.” He roams through two domains: experimental music and visual art combined with sound. “Sound is the central thing for me. What interests me most is making these two domains meet,” he says. The results vary in expression. One week he might be performing a concert, the next week showing off his latest “sound sculptures” or exhibit installations, with additional time spent composing and performing in collaboration with a choreographer.

SOUND (OR NO SOUND)

Paradoxically, some of his works have no audible sound. Many feature broken speakers, such as “Speaker Flag, Broken Flag,” which is a speaker set inside the Korean flag. “For Interpreters” is a video that uses sign language, leaving viewers to imagine the sound. It plays on the idea of “representing sound without sound.”

Over the years, Klemensiewicz has exhibited and performed at major venues such as the Nam June Paik Art Center in Yongin, Gyeonggi Province, the National Hangeul Museum and the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. But he likes to work in small, experimental spaces in the Hongik University area, where he started out and still lives.

One of his first projects in Korea was “Takeout Drawing,” a residency in 2014 at a café of the same name in Itaewon, Seoul. Every day for two months, he performed either an impromptu solo concert, a formal concert with guest performers, or oftentimes just a rehearsal. The lack of structure befuddled some customers. “What was interesting for me was playing with the line between a proper concert and a rehearsal – an ambiguous situation where no one knew what was happening,” he says.

Born in Marseille, France, and living in Seoul since 2013, Rémi Klemensiewicz is known as a sound artist or intermedia artist. He explores ways to bring together the worlds of sound and visuals, and analyzes the difference between existence and interpretation, moving freely between exhibitions, live performances and stage music.

ENIGMAS

Klemensiewicz seemingly enjoys paradoxes and ambiguity, which not only inform his work but are the very qualities of the Korean language and culture that intrigue him. For example, the use of honorifics in Korean is generally considered a way to maintain a proper social distance between individuals. But Klemensiewicz feels there is more nuance present.

“When I’m around students and their teachers, I can notice the students’ respectful behavior not only in their words but also in their movements and other subtle things,” he says. “But despite the strict rules, there’s an almost family-like relationship between them. This is contrary to what I felt in France. We would use first names with our teachers and talk like friends, but I seldom felt close to them.”

He also finds a paradox in the exterior appearances of his homeland and Korea. Although Paris and other places around France impress visitors with their beauty, Klemensiewicz feels tradition and spirituality have been lost. He finds Korea to be the opposite. “When I first arrived here, I saw so many chaotic buildings. But despite the visual chaos, I felt there was order in people’s minds,” he says. “If I compare the two countries, in France I feel there is order on the outside and chaos within. In Korea, there is chaos on the surface and order inside, and there’s a connection with tradition and the past.”

Such discoveries beguile and stimulate him and keep him in Korea. For visa reasons, however, he had to spend much of the pandemic period in France. While there, he stayed in the countryside, and when he returned to Seoul recently, he realized anew how its concrete and natural features intricately overlap. Subway lines transport riders to the foot of surrounding mountains and a bike path parallels the Han River with huge apartment complexes looming a stone’s throw away. “To me, this is crazy,” he says, laughing.

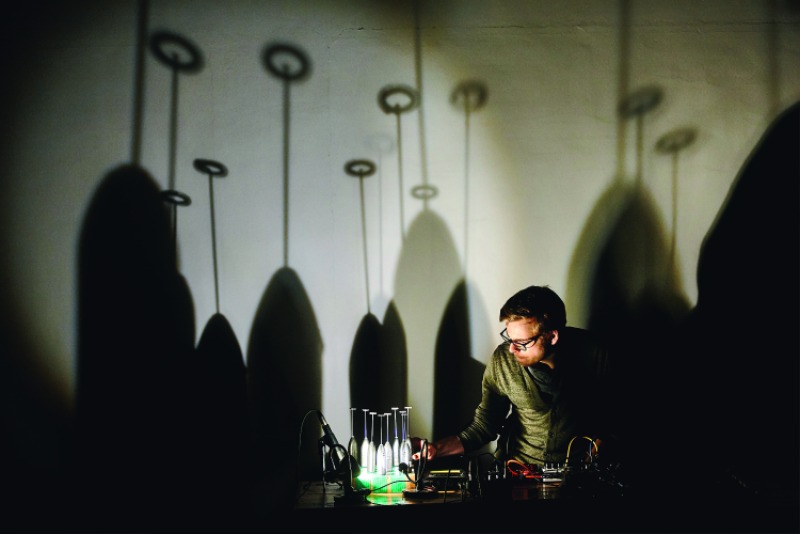

Klemensiewicz performs “Handmixer,” a part of the Contemporary NonMusic Vol. 11 Series, on November 19, 2019 at Donquixote, an art space in Suncheon, South Jeolla Province. © Artspace Donquixote

LIVELIHOOD

While spending much of the COVID period in the French countryside, he used the downtime to make online Korean language lessons for French YouTube users. What started out as a diversion suggested by a friend turned into a serious endeavor. He eventually spent months planning and writing lessons, with a long introduction to Hangeul, the Korean alphabet.

The tutorials are based on his own experience. An artist working with sound, Klemensiewicz recognizes most of his works have no commercial potential. Language lessons – French to Koreans and vice versa – have enabled him to ignore suggestions that he should find a regular job.

Klemensiewicz says teaching is for balance, but he ultimately likes to experiment with language. Besides, he admires the visual qualities of Hangeul and has incorporated them into his work. “Sound Word Series,” presented at the Nam June Paik Art Center in 2018, features Hangeul words composed of speakers and cables. As part of the exhibition, he held performances in a cage with guest musicians; together they improvised using only four notes – C, A, G, E.

Teaching art classes has also provided Klemensiewicz some stability while opening up new possibilities. He started with art workshops for middle-school students at the Nam June Paik Art Center and now has regular classes at Hello Museum in Seongsu-dong, Seoul, where he teaches children about sound and visuals. Teaching a course in “sound design” at PaTI (Paju Typography Institute) also led to his next project, a collaborative work with the Korea Contemporary Dance Company.

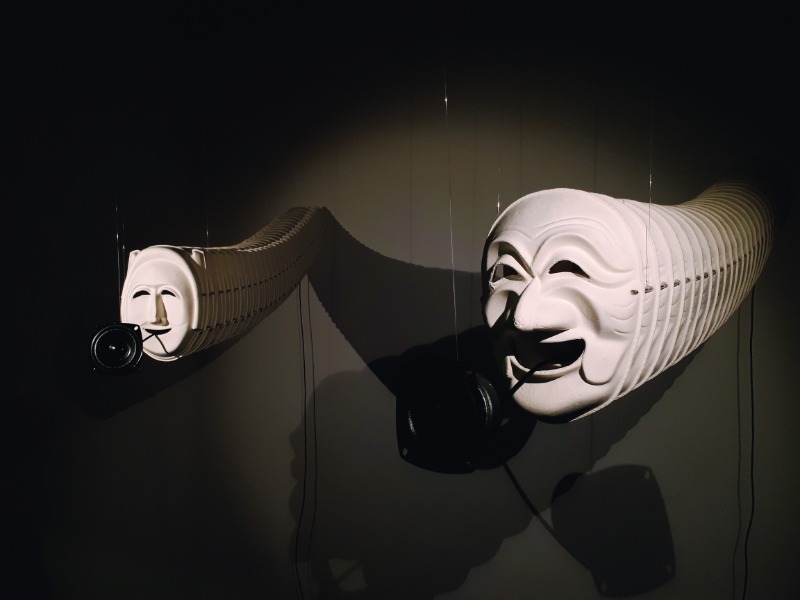

“Interpreted Masks,” presented by Klemensiewicz at the exhibition “Project Hope?” held October 12-28, 2017 at Post Territory Ujeongguk, a cultural complex in Seoul. It consists of paper masks, speakers, cables and sound. © Rémi Klemensiewicz

PROGRESS

Although Klemensiewicz’s work is difficult to define, there is one constant: everything he sees and hears somehow seeps into his art. Against that backdrop, his almost instinctive attraction to Korea, which is constantly in motion, is easier to understand.

When he first arrived, he had a honeymoon period, which is typical. “I could sleep on the floor and be happy. I could eat jjajangmyeon everyday and be happy. It could rain everyday and I would still be happy,” he recalls. As time passed, he started to be bothered by what he calls the “rhythms of work,” or the difficulty separating work from his private life. But he admits that he isn’t very good at separating work from leisure anyway because, the way he sees it, art is related to everything. “Besides, when I’m doing an exhibition or concert, I love doing it so much that I don’t really consider it as work.”

After nine years in Korea, Klemensiewicz’s life so far seems to resemble an experimental artwork in the making, with an emphasis on the process in the spirit of the Fluxus artists who have influenced him. It’s no surprise, then, that he is currently submerged in an exchange project with choreographer Ro Kyung-ae and his alma mater in France. It requires him to create and perform music for dancers who cannot hear.