Fusing Western pop with gugak (traditional Korean music), a new genre nicknamed “Joseon pop” is coming under the spotlight. This musical variant is poised to expand the boundaries of K-pop, but it didn’t appear overnight.

sEODo Band performs at Olympic Park in Seoul in December 2021, during a nationwide concert tour, a follow-up to “Pungnyu Daejang” (Masters of Arts), a TV audition program for pop and gugak crossovers on the cable network JTBC. The popular survival show brought traditional music to the attention of a wider general audience.

© JTBC, ATTRAKT MJTBC

“Gugak is the music of Koreans, but it’s also the music farthest from Koreans,” said a novelist and music lover, pointing to the reality of traditional Korean music since the 20th century. The native music of Koreans, although shared and passed down for centuries, had departed so far from contemporary sensibilities as to be nearly extinguished. It had become deeply engraved in people’s minds as quaint and out of date.

This preconception was a major obstacle to the transformation and evolution of traditional Korean music, but ironically, it also served as a catalyst for the recent “Joseon pop” trend. When traditional Korean music came out of obscurity in a different outfit, people found it strikingly stylish. But this should not be seen as an unprecedented turn of events: traditional Korean music has constantly been evolving with fresh ideas and renewed sensibilities. Now, it’s coming into the limelight after long years of obscurity.

Kim Duk Soo (second from left) and the Cheong Bae Traditional Art Troupe give a joint performance at Gwanghwamun Art Hall in October 2015. Kim Duk Soo & Samulnori, a percussion quartet organized in 1978, gave numerous concerts at home and abroad, enjoying huge popularity. The Cheong Bae Traditional Art Troupe has been dedicated to creating its own music inspired by traditional Korean performing arts for over 20 years.

© Samulnori Hanullim

Support for Preservation

Since the late 20th century, the government’s policy to preserve traditional music has been critical to its survival. Preservation enabled the creation of a new music rooted in tradition. In any country, traditional music tends to be treated as irrelevant to contemporary life, and the same fate has repeatedly threatened Korea’s traditional music. The Japanese colonial period (1910-1945) was the dark age, and the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 led to the destruction of related resources, including musicians. Postwar political turmoil and economic hardship further depleted the potential for regeneration. During the rush of industrialization and urbanization that began in the 1960s, traditional music remained at the fringes, belittled as a premodern art form.

Throughout recurring crises, efforts to preserve the legacy of traditional music continued, albeit inconspicuously. During the Japanese colonial era, these efforts were headed by the Music Institute of the Yi Royal Household. Divested of sovereignty, the Joseon Dynasty had been demoted to the “Yi Royal Household” and music performances for court ceremonies were about to be reduced or abolished. But despite the hostile climate, the royal music institute managed to recruit students and teach them court music to keep the tradition alive. During the Korean War, which broke out a few years after liberation and the establishment of the Republic of Korea, the National Gugak Center was founded in Busan, the wartime capital. It gathered under its roof the remnants of musical rsources and musicians scattered across the war-torn country. After the armistice in 1953, it was relocated to Seoul and has since grown into the central institution responsible for the preservation of traditional music and its modern reinterpretation and creation.

The enforcement of the Cultural Heritage Protection Act in 1962 was also crucial. Based on the law, the National Intangible Cultural Heritage system was introduced to designate areas of traditional culture and arts for preservation and provide support for practitioners qualified to be a “title holder” or “certified trainee.” The areas of traditional music with such official recognition include Jongmyo Jeryeak (royal ancestral ritual music), gagok (lyric song cycles), pansori (narrative song), daegeum sanjo (solo on the transverse bamboo f lute) and Gyeonggi minyo (folk songs of the Gyeonggi region), among others. Interestingly, many of the performers leading the recent reappraisal of traditional Korean music are certified trainees in arts designated as National Intangible Cultural Heritage: Black String’s Yoon Jeong Heo was trained in geomungo sanjo (solo on the six-stringed zither); Jambinai’s Ilwoo Lee in piri jeongak (court music on the double-reed oboe) and daechwita (processional music); LEENALCHI’s Ahn Yi Ho in pansori; and singer Lee Hee-moon in Gyeonggi folk songs.

Coreyah, a gugak crossover group, holds its concert “Clap & Applause” (Baksumugok) at Guri Art Hall in September 2020, celebrating its 10th anniversary. The group presents a unique fusion of pop and ethnic music from around the world, playing up the characteristics of traditional instruments.

© Guri Cultural Foundation

Popular Appeal

The Department of Korean Music at Seoul National University, founded in 1959, paved the way for traditional music to become a subject of academic research. It inspired other universities across the country to open similar departments, which increased greatly in number in the 1970s and 1980s. They produced graduates who stood out in the music scene, spearheading the development of traditional music.

Unlike the previous generation, who saw tradition endangered amid the turbulence of the 20th century, these college-educated musicians believed that beyond preservation and transmission, it was important to breathe new life into traditional music for wider appeal. They started to compose creative works using elements of traditional music tweaked with contemporary style.

The definition of “creative” was quite broad at the time as it included new works based on the motifs of well-known folk songs or pansori pieces, as well as arrangements of Western classical music for traditional instruments.

Specifically, samulnori (ensemble of four percussion instruments) appeared in the late 1970s and played a pivotal role in making traditional music popular. Having evolved from the rhythmsof farmers’ band music played in rural communities, samulnori is a lively performance of the buk (barrel drum), janggu (double-headed drum), kkwaenggwari (small gong) and jing (gong). Young musicians gave exciting performances incorporating characteristic elements of these four instruments, stirring audiences to respond to the uplifting rhythms and bringing traditional music back from the fringes to which it had long been banished.

Transformation

In the 1980s, when the pop music market was growing rapidly, a popular version of minyo with the distinct rhythms and melodies of traditional music emerged. “Gugak pop songs” took root as a genre of popular music, contributing to broader enjoyment of traditional music. The accompaniments combining Korean and Western instruments paved the ground for the emergence of “fusion gugak” in the 1990s.

The wave of globalization that swept the country around the 1988 Seoul Olympics also spurred the evolution of gugak. With an open market and new trade order, and Western culture permeating everyday life, Koreans started to open their eyes to their own culture. Big hits in this social milieu include Bae Il-ho’s song “Sintoburi” (1993). The title means “body and soil cannot be separated,” hence encouragng the consumption of home-grown foods. “Seopyeonje,” a film directed by Im Kwon-taek depicting pansori singers, was released the same year and achieved record-high ticket sales, earning kudos as a “national movie.” Around the same time, a pharmaceutical advertisement featuring the master pansori singer Park Dong-jin (1916-2003) shouting, “Cherish what’s ours!” yielded a buzzword that remained popular for a while.

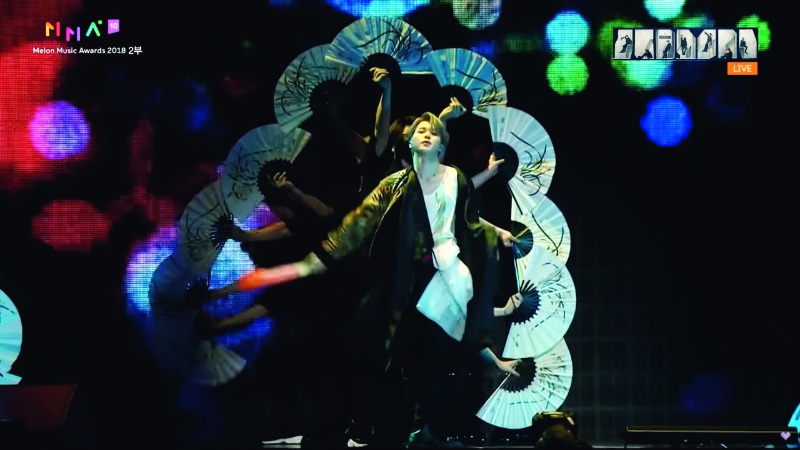

Jimin of BTS performs a traditional fan dance at the 2018 Melon Music Awards. At the year-end event, BTS also presented “IDOL,” featuring J-HOPE’s three-drum dance and Jungkook’s mask dance, drawing an enthusiastic response from the audience.

© Kakao Entertainment Corp.

SUGA of BTS appears in the music video for “Daechwita,” the title track of his second mixtape, “D-2” (2020). The song deftly combines trap beats and the sound of traditional instruments from daechwita, the music for royal processions of the Joseon Dynasty.

© HYBE Co., Ltd.

On the occasion of Seoul’s 600th anniversary as the capital of Korea, the government designated 1994 as “Visit Korea Year” and the “Year of Gugak” to invigorate the tourism industry. To attract international visitors, traditional music was touted as one of the country’s major cultural products. A few years later, however, the Asian financial crisis dealt a severe blow to the art and culture circles. Many traditional musicians were forced to think about what kind of music they had to pursue to make a living.

In the late 1990s, thanks to the spread of the internet, traditional musicians as well as the general public were exposed to a variety of music from other countries. They came to learn there was a genre called “world music,” created based on each country’s musical traditions. Music from South Asia, Africa and other areas became a rich source of inspiration. Previously, the traditional Korean music repertoire for overseas performances had mostly been limited to time-honored classics. As more fusion styles came to be presented at international music festivals, audiences responded favorably. At the forefront of the trend were Percussion Ensemble Puri, a group led by the composer Won Il, and the world music group GongMyoung.

Gradually, the notion that creative succession of tradition involves transformation and modification became widespread. This is consistent with UNESCO’s decision to inscribe the Korean folk song “Arirang” on the list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, explaining that the old song is still universally sung by Koreans and transmitted in various versions created by individuals and communities.

A still cut from singer Lee Hee-moon’s online concert “Minyo,” streamed live on the internet portal Naver in July 2021. Released ahead of the concert, the image represents a fantastic visualization of Minyo, the eponymous character that Lee created. The character’s name is a parody of minyo, traditional folk songs.

Courtesy of Lee Hee Moon Company

Collaboration and Synergy

“Joseon pop” grew out of this long history and background, which provided a rich soil for the birth of bands better known overseas than at home, including Black String, Jambinai and LEENALCHI. The success of the Yeo Woo Rak Festival grew out of this same soil. The annual festival, hosted by the National Theater of Korea, started in 2010 as a domestic event but has now grown into a world music festival overflowing with the creative ideas and inspirations of young musicians.

Recently, artists in other fields and the general public have been seeing traditional music in aremarkably different light. The TV audition program “Pungnyu Daejang” (Masters of Arts), which aired on JTBC from September through December 2021, showcased the unrestrained experimentation of young musicians, leaving viewers raving over their unfamiliar but stylish music. Another new trend is active collaboration between traditional musicians and artists in other genres, such as theater, dance, film, musicals and fine art, all seeking to create something different. Singer Lee Hee-moon, who has worked closely with many artists in fashion, the visual arts and music videos, said in a recent interview, “It’s undoubtedly important to preserve our traditional music intact, but I often think of it as a secret weapon to bring creative change to other genres of art.”

It remains to be seen whether “Joseon pop” will be able to enhance its appeal for global fans of world music who look for unique fare from around the planet.