An isolated village on the southern side of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) is a remnant of the Korean War armistice agreement of 1953. Two award-winning South Korean artists have reinterpreted the village for their latest collaboration. The aim, as the duo explain, was “to reflect on the ironic, institutionalized conflicts and tensions that beset human history in general.”

The division of Korea may be a subject that most artists from this country want to avoid. It is typically deemed too self-evident for much texture, or overly grandiose to encapsulate. Those who take up the subject must often endure criticism that they chose an all too familiar episode. International artists look to their Korean cohorts for cues, but few step forward to venture into the theme from a faraway land.

Moon Kyung-won and Jeon Joon-ho were undaunted. They boldly put on “News from Nowhere – Freedom Village,” a multi-faceted exhibition that recently ended at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) in Seoul. Their next stop this year is the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, Japan (May 3-September 11), and shortly afterwards, the London-based Artangel and then the Art Sonje Centre, back in Seoul. A U.S. showing is also being discussed.

Moon teaches Western painting at Ewha Womans University in Seoul and Jeon is based in Yeongdo, a seaside area of his native Busan. They have collaborated since 2009, forming a rare duo on the Korean fine arts scene. They constantly explore the role of art in coping with the universal issues of mankind, such as contradictions of capitalism, historical tragedies and climate change.

Moon Kyung-won (left) and Jeon Joon-ho pose with a part of their collaborative project, “News from Nowhere – Freedom Village,” displayed at the Seoul branch of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art for the “MMCA Hyundai Motor Series 2021” (September 3, 2021-February 20, 2022). The duo defined Freedom Village, the only civilian settlement on the southern side of the Demilitarized Zone, as a place created by human confrontation and conflict – a symbol of the isolation endured by numerous people amid the coronavirus pandemic.

LOOK BACK

“News from Nowhere” is a long-term project that has had several iterations. The title is from the eponymous utopian novel written by William Morris (1834-1896), an artist, designer and socialist pioneer who led the British Arts and Crafts Movement. In the novel, the narrator falls asleep and awakens in a future agrarian society that has no class, no systems of money or authority, no private property and no courts or prisons. Through the novel, Morris hurled scathing criticism at the social problems of his time. Moon and Jeon borrowed not only the title, but also the novel’s style of keenly dissecting the present from a perch in the future. “Our future-based view is not an attempt to diagnose the future but an effort to discuss the present agenda,” they explain.

The duo’s “News from Nowhere” premiered in 2012 at documenta, a contemporary art exhibition held every five years in Kassel, Germany. The subtitle then was “The End of the World.” The exhibition led them to win the Artist of the Year 2012 Award from the MMCA and the Noon Award at the 9th Gwangju Biennale in the same year. In the ensuing years, the project, with input from other artists, appeared under different subtitles in various forms, including video works, installations, archival photographs and publications.

Previous venues include the Sullivan Galleries at the Art Institute of Chicago in the United States (2013); the Migros Museum of Contemporary Art in Zürich, Switzerland (2015); and Tate Liverpool in the United Kingdom (2018). The duo also represented the Korean Pavilion at the 2015 Venice Biennale, presenting a multi-channel film installation titled “The Ways of Folding Space & Flying.” “News from Nowhere” had never appeared in Korea on an expansive scale before the artists were picked for the MMCA Hyundai Motor Series 2021. Starting in 2014, Hyundai Motor has annually sponsored a solo exhibition by a leading Korean artist at the MMCA. The previous pick was Yang Haegue, an installation artist of international renown. As to why they chose to reinterpret the division of Korea through a unique civilian settlement within the DMZ, Jeon said, “This project has reflected the identity, history and pressing issues of local regions in each different country and city. We thought long and hard about what to do about Korea. We wanted to break from the cliché about a divided nation. But after all, it was a sort of duty that any Korean artist ought to fulfill. So we decided not to make it a simple ref lection of the political situation in Korea, but an immersive experience for visitors to help them think of the universal history of humankind.”

“News from Nowhere – Freedom Village” revolves around huge back-to-back screens that show different videos. They help immerse viewers in the installation art, comprising lights, sounds and images appearing on the screens connecting with the exhibition space. On the screen, “A,” a man who longs for freedom (played by actor Park Jeong-min), roams around in the mountains, looking for wild plants to study. © CJY Art Studio

BYPRODUCT OF CONFLICT

“News from Nowhere – Freedom Village” refers to Daeseong-dong, the only civilian residential settlement on the southern side of the DMZ, the heavily fortified strip of land running across the Korean Peninsula separating the North and South.

Everything about the village is atypical. Its name doesn’t ascribe to the usual rendition of topographic characteristics or legends, and despite being inside South Korean territory, the village is controlled by the UN Command. Under the Korean War armistice agreement of 1953, both sides of the war recognized Daesong-dong in the South and Kijong-dong in the North as the only civilian residential areas within the DMZ. Afterwards, the two villages were given new names: “Freedom Village” and “Peace Village,” respectively. But the benign monikers were outright misleading; the villages became emblems of Cold War vitriol.

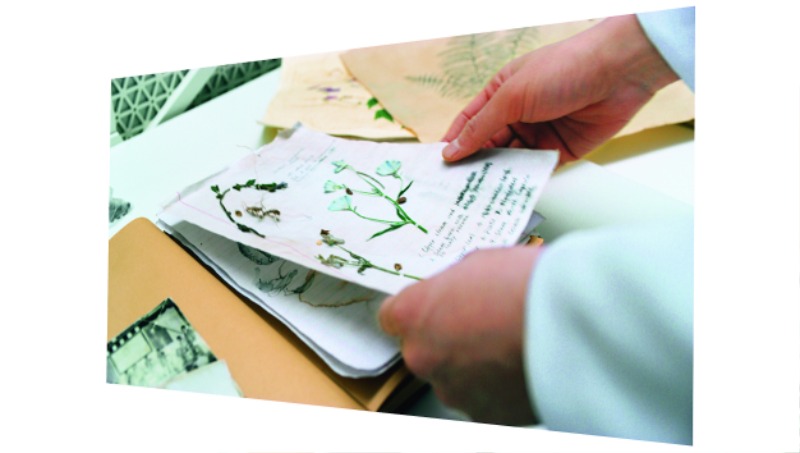

A still from “News from Nowhere – Freedom Village” shows “A,” an amateur botanist, making plant specimens. Having never ventured outside of his native village, he collects and studies plants. © MOON Kyungwon & JEON Joonho

In the hope of making his existence known to the outside world, “A” flies balloons carrying his plant specimens. He thus begins communication with “B,” another young man who lives in the future, occupying a small, hightech facility. © MOON Kyungwon & JEON Joonho

Yeongsanjae, or the Rites of Vulture Peak, which was placed on UNESCO’s List of Intangible Cultural Heritage Currently, some 200 people in 49 households live in Freedom Village, surrounded by heavily armed troops and barbed wire fences due to its close proximity to North Korea. Private property is not allowed in the village. There’s a midnight curfew and roll calls are regularly held. The residents’ livelihood is mostly farming or raising livestock; commercial ventures don’t exist. Residents are afforded tax benefits and men are exempted from compulsory military service. If a female resident marries a non-villager, she must leave the village, but a male resident can stay if he marries an outsider.

The two artists didn’t depict the village merely as a byproduct of the geopolitical situation of the Korean Peninsula. Rather, they used it as a symbol of a world molded by confrontation and conflict. Moon said, “At first, we were thinking of setting the project in an urban area with a more clear-cut identity. But we accepted Freedom Village as our keyword because it is an extremely unrealistic space for us, blurring the border between reality and fiction.” Jeon agreed, saying, “Perhaps for the last seven decades, the residents of this village have lived in a more disastrous situation than the pandemic we are currently in. In the present, when humanity is waging a war on COVID that has lasted for more than two years, the isolation of this village seems like the right keyword that can help us draw a universal consensus and look back on our own lives.”

The result is a significant example of how South Korean artists are approaching the DMZ, going beyond the “easy path” of reiterating notions of ideological division and conflict.

INFINITE LOOP

The exhibition was an ambitious project, consisting of videos, installations, archives, photos, a huge painting and a mobile platform for affiliate programs. The centerpiece was two 15-minute videos shown on large, back-to-back screens. On the first screen, actor Park Jeong-min appeared as “A,” a 32-year-old amateur botanist and village native. “A” studies indigenous plants growing in the DMZ but has never ventured outside of his birthplace.

To make his existence known to the outside world, “A” floats a balloon carrying plant specimens that he has collected and studied, along with notes about his daily life. The balloon lands near “B,” a man in his early 20s on the other screen.

“B,” played by Jinyoung of boyband GOT7, is living in the future. He occupies a small, high-tech facility, occasionally glimpsing the outside. Startled and deeply puzzled, “B” scrutinizes the balloon for a few days before he finally musters the courage to remove its contents. Thereafter, he continuously receives balloons from “A,” persuading him to step outside of his facility. The spiritual link between the two young men turns out to have no endpoint, reminiscent of the infinite loop of time.

Past these videos were photos of Freedom Village, provided by the National Archives of Korea with one proviso. “We were permitted to use images on condition that we would protect the anonymity of the people in the photos. So we obscured faces or superimposed new images on the originals by combining several different images together,” Moon explained. “Sometimes, we put face masks on those people’s faces through airbrushing technology, which resulted in a kind of masterstroke, as if it foretold the current pandemic situation.”

In the last exhibition room, a snow-covered forest where “A” searched for plants was depicted in a huge landscape painting. Moon labored for more than six months on the canvas, which measures 2.92 meters by 4.25 meters. The hyper-realistic oil piece is so precise and elaborate that it could almost be mistaken for a photo. A quote from John Berger (1926 -2017), a British art critic, painter and poet, served as a thought-provoking epilogue for visitors. It read:

“Sometimes a landscape seems to be less a setting for the life of its inhabitants than a curtain behind which their struggles, achievements and accidents take place. For those who are behind the curtain, landmarks are no longer only geographic but also biographical and personal.”

“Mobile Agora,” a set of cube shaped, stainless steel objects placed outside the exhibition hall, can easily be disassembled and reassembled. It served as a venue for monthly discussions by experts in architecture, science, design and the humanities during the exhibition.

“Landscape,” an oil and acrylic painting by Moon Kyung-won, measuring 292 x 425 cm, depicts a barren place where “A” roams. It recalls an area in Paju, Gyeonggi Province, adjoining the DMZ. The scenery resembles an image of Freedom Village provided by the National Archives of Korea. © CJY Art Studio