The growing diversity of performance venues, well-established theater festivals in different regions

across the country, and increasingly active international exchanges are all serving to inject greater

vitality into the Korean theater scene. At the heart of this burgeoning dynamism is a new

generation of directors who are avidly exploring contemporary subjects.

The Orphan of Zhao” (2015), adapted and directed by Koh Sun-woong. The classical Chinese tragedy was turned into a Korean-style musical.

The Korean theater scene in the 2000s has been remarkably vibrant. Theatrical artists of the younger generation have shown a steady commitment to a broader scope of creative activity, and the platform for producing and staging plays has grown substantially in terms of both scale and number.

Dynamic Source of Energy

Theater festivals big and small are held throughout the year, not only in Daehangno, the “mecca of Korean theater,” but in other parts of Seoul and various other cities around the country as well. Though the larger theaters may be concentrated in Seoul, several big theater festivals have taken root in other parts of the country, such as the Miryang Summer Performing Arts Festival, the Chuncheon International Mime Festival, and the Geochang International Festival of Theatre.

The role of public theaters is also evolving. While they previously served mostly as favorable, and affordable, venues for private theatrical troupes, for the past decade or so public theaters have been actively mounting their own productions. In addition to venues operated by the arts and culture foundations affiliated with big business corporations, such as the LG Arts Center and the Doosan Art Center, publicly-funded theaters like the National Theater of Korea,the Myeongdong Theater, and the Namsan Arts Center are also presenting their own productions around the year.

Another emerging trend is the rise in 1 “The Orphan of Zhao” (2015), adapted and directed by Koh Sun-woong. The classical Chinese tragedy was turned into a Korean-style musical. 2 “Killbeth” (2010) is an adaptation of Shakespeare’s “Macbeth,” directed by Koh Sun-woong. The interplay between tragic tension and comic relief amid the spectacular action creates an explosive theatrical energy. site-specific performances held outdoors in the streets and everyday spaces as well as the growing diversity of cultural spaces. In Seoul, there is Takeout Drawing in Hannam-dong, a venue for exhibitions and performing arts as well as a workshop and café, and the Indie Art Hall GONG, housed in a remodeled former factory building in the industrial district of Yeongdeungpo, western Seoul. Commercial facilities in older residential districts are also being repurposed into cultural spaces where young theatrical artists can launch their creative experiments.

At the same time, wide-ranging exchanges with other countries are helping to broaden the scale and content of Korean theater. The Asian Arts Theatre at the Asia Culture Center in Gwangju, which was opened in autumn 2015, has staged original works with Asia-related themes created by new and veteran artists who are active in Asia and Europe. More Korean plays are advancing into overseas markets, meeting audiences not only in Asia and Europe, but other regions like South America. The scope of international collaboration is also expanding, involving foreign directors working with Korean actors, Korean directors taking on projects overseas, and joint productions between Korean and foreign theater companies.

From ‘Who Am I?’ to the ‘Here and Now’

It may be helpful to introduce three directors who have risen to prominence riding on the dynamism of Korean theater in recent years. But before telling their stories, we need to go a bit further back in time.

As in most other Asian countries, the introduction of Western drama marked the beginnings of modern theater in Korea. At that time, directors grappled with the issue of theatri-cal identity and the problem of integrating elements of modern Western drama with traditional Korean theater. Major works by 20th century masters, namely Kim Jung-ok, Heo Gyu, Son Jin-chaek, Oh Tae-seok, and Lee Youn-taek, delved into the identity of Korean theater based on the nation’s cultural traditions. They adapted Western classics, such as Greek tragedies and Shakespeare’s plays, into the language of traditional Korean theater, while recreating on stage the traditional rituals and entertainment which had originally been performed in outdoor spaces. Through these endeavors, they incorporated various elements of traditional Korean performing arts, such as gut (shaman rites), masked dance dramas, folk songs, and pansori (narrative song), into modern plays.

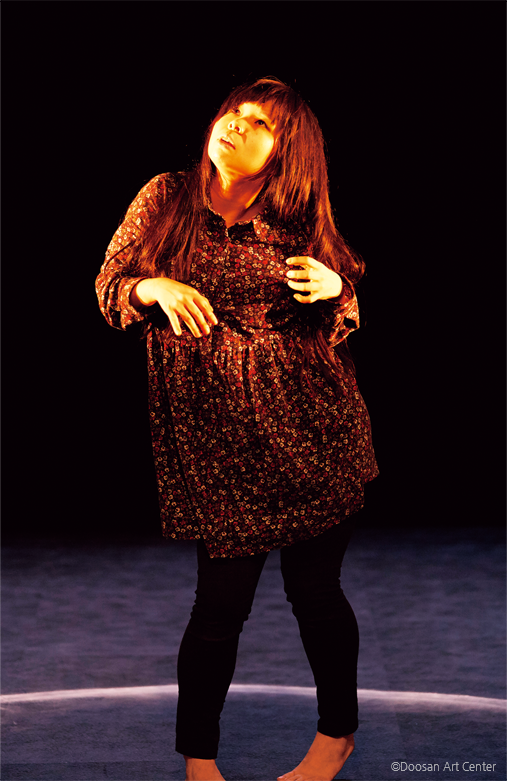

“Killbeth” (2010) is an adaptation of Shakespeare’s “Macbeth,” directed by Koh Sun-woong. The interplay between tragic tension and comic relief amid the spectacular action creates an explosive theatrical energy.

In the 2000s, however, playwrights and directors clearly departed from the approaches of their predecessors. Rather than identity, they were concerned more with the issue of contemporaneity. Instead of being burdened with the question of theatrical identity and concerns about producing plays in languages that might not be their own, they struggled with the validity of their works in the here and now, that is, whether they were dealing with the genuine issues of their own era.

Park Kun-hyung is a playwright and director at the forefront of the new generation of theatrical artists whose main focus is on contemporaneous themes. “Beautiful Youth” is the work that brought him fame. Belying its title, the play is about a young man struggling with a disintegrating family life, not accepted at school or in society. When it was first staged in 1999 at Hyehwa-dong No. 1, one of the smallest theaters in Daehangno with less than 100 seats, the black box stage was basically empty except for two long benches. It is literally a “destitute” play. Spread a blanket and set a table with soju and dried snacks, and the stage is transformed into the room where the father and son reside; put up an ad poster on the wall, and it turns into a shabby bar. Park candidly illuminates the story of those living on the outermost margins of society in an age of abundance. “Why build a huge house on the stage when our lives aren’t like that?” he says. At times, theatrical omission, distortion, and exaggeration stand out in his works, but these features come across as a hyper-realistic representation and frightening reminder of the harsh reality of the times we live in.

Many of Park’s works are about the family, which has ceased to function as a bulwark against today’s increasingly hostile world. They tell harrowing tales of dysfunctional families, crumbling family relationships, and people pushed to the periphery of society. But his plays do not stop at narrating the stories of impaired family ties; they portray the pain and suffering lurking in all corners of society through a tense interplay between cynicism and humanism.

“Ghost Walk” from the play “Namsan Documenta: Practice–Theatre Version” (2014), produced by Lee Kyung-sung and Creative VaQi. The audience and actors take an hour-long walk around Mt. Nam before the actual play, encountering each other along the way.

Simple, Yet Fluid

Whereas Park probes the issue of the

here and now, Koh Sun-woong’s works are

mostly about theatricality. Also a playwright

and director, Koh is adept at reinterpreting

and adapting classical works in his own

language and style.

Koh’s 2010 work “Killbeth,” an adaption

of Shakespeare’s “Macbeth,” is set in an

unknown time and place of endless fighting

and killing. The title is a play on the

name Macbeth, which sounds similar to the Korean slang for “indiscriminate slashing.”

As the title suggests, the play starts with

a violent confrontation of clashing swords

and continues throughout with the vociferous

sounds of people’s cries and swordplay,

at times in hand-to-hand combat, filling

the stage. It would be a mistake, though, to

think that Koh has turned a Shakespearean

tragedy into a spectacular sword fight that

is nothing more than a feast for the eyes. It

is true that the play highlights movements

that accentuate the bodies of the actors

— the sweat running down their bodies

seems palpable. But just as striking is the

rapid-fire dialogue that twists the conventional

theatrical situation. It deliberately

destroys the rhythm of everyday conversation

or tragedy, creating a clear rhythm of

its own. The words carried by the rhythm

at times end in an incredible letdown

after mounting tension, creating comedic

relief, or a light-heartedness that contrasts

with the serious drama, leading to a

state of near hysteria. The brilliant interplay

between tension and relaxation in the bodily

movements and words, and their rhythmic

interchange, exudes a theatrical energy

that leaves the audience almost breathless.

Koh’s most recent work “The Orphan

of Zhao” (2015), eloquently demonstrates

just how his theatrical style brims with witty

sensibility and can also pierce the heart of

human suffering. Based on the classical

Chinese play, “The Great Revenge of the

Orphan of Zhao,” attributed to Ji Junxiang,

the play depicts a tale of vengeance. All 300

members of the Zhao clan are slaughtered except for a newborn baby, and many people sacrifice their lives to save the orphan, who

grows up to seek revenge against the enemy that exterminated his family. Koh uses sparse

stage props, movement, and dialogue in this horrific odyssey of vengeance. A single red curtain

encircles the empty stage.

“Before After” (2015), directed by Lee Kyung-sung, deals with the Sewol ferry disaster of 2014.Through the tragic and shocking incident, it delves into the sense of pain.

Events and actions are codified into simple movements and

props. All the characters in the play choose death for the sake of the orphan’s revenge. Koh

does not glorify their deaths as valiant deeds in the name of morality or justice. Nor does

he hint at the futility of the vendetta. Instead, through simple yet fluid motion and dialogue,

he portrays the characters’ attachment to life and fear of death as well as their fierce inner

conflict, torment, and resolve, as they eventually come to accept their fate. It is human to

shun involvement in such a tragedy; it is also human to make a resolute choice when faced

with a moment of life or death.

Scenes from “Beautiful Youth,” which brought high acclaim to director Park Kun-hyung. Since its premiere in 1999, the play has been restaged many times with different casts. Belying its title, it portrays the harsh reality of today’s Korean society where young people no longer dream of the future

In the 2000s, however, playwrights and directors have clearly departed from the approaches of their predecessors. Instead of being burdened with the question of theatrical identity and concerns about producing plays in languages that might not be their own, they struggled with the validity of their works in the here and now, that is, whether they were dealing with the genuine issues of their own era.

The Ethics of Sensibility

Although he is just over 30, the modifier “young” is no longer attached to director Lee Kyung-sung, who is acclaimed for his distinctive theatrical methodology. The theater group Creative VaQi, which he heads, first received attention for its site-specific plays staged in everyday spaces such as crosswalks or open squares.

But Lee is not just a young director recognized for his new approaches or creative experiments. “Namsan Documenta: Practice–Theatre Version” (2014), produced by Lee and Creative VaQi, features the Namsan Arts Center as its principal character. When the theater first opened in 1962 as the Drama Center, it became a major venue for modern theater but thereafter faded into obscurity until its recent reopening. “Namsan Documenta” is based on extensive research of public and private archives related to the history of the theater and its location at the foothills of Namsan, or Mt. Nam. The play includes edited versions of video archives that were discovered during research and a different take on a scene from the theater’s opening performance, “Hamlet.” Also included is a fictional interview that summons the theater and Namsan as witnesses to events in modern Korean history. Although a documentary play, as the title suggests, it is more than a mere compilation of historical records. It ingeniously crosses the boundaries between presentation and reenactment, fact and fiction, focusing on intellectual and sensory exploration of the theatrical space and the essence of theatrical production in the here and now.

Scenes from “Beautiful Youth,” which brought high acclaim to director Park Kun-hyung. Since its premiere in 1999, the play has been restaged many times with different casts. Belying its title, it portrays the harsh reality of today’s Korean society where young people no longer dream of the future.

Lee’s more recent work, “Before After”(2015), displays a heightened level of maturity. The play deals with the Sewol ferry disaster of 2014. It is not just a reenactment of the tragic and shocking incident, nor does it attempt to search for answers as to why it happened or to trace its ongoing consequences. Rather, it asks about the pain surrounding this catastrophic disaster. People living in today’s high-tech society are frequently exposed to fatal incidents and natural disasters, and consume news of such events through the media thanks to technological developments. In times when the atrocities of war are broadcast live worldwide, tragic events are consumed through images. “Before After” seeks to put an end to such consumption of pain. The play centers on an actor coping with the death of her father, and sheds light on the personal pain of each individual through narrations and reenactments. Real-time images of the play are projected to simultaneously show what is happening on stage from another angle. The play garnered considerable attention for its composed and meticulous rendering of the question of how much we can empathize with other people’s pain and sense it with our whole bodies.