Photography arrived in Korea in the late 19th century, provoking both wonder and fear. The new technology, coinciding with economic advancement, eventually enriched the nation’s cultural life and spurred the development of related industries. Today, virtually everyone is a photographer and taking pictures is a commonplace activity. Younger generations are more familiar with creating images than with writing.

“Seesawing Young Ladies”

Florian Demange, 1910s. Dry glass plate, 17.5 x 12.5 cm. © Jeong Seong-gil

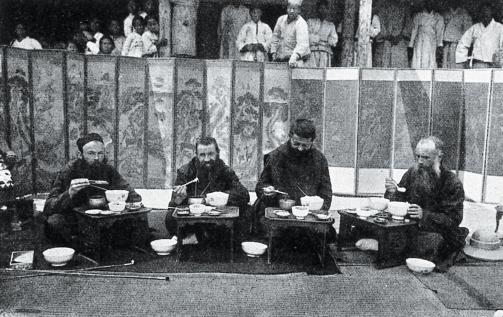

The First Dinner”

Norbert Weber, OSB, 1911. Dry glass plate.

© Benedict Press Waegwan 2012

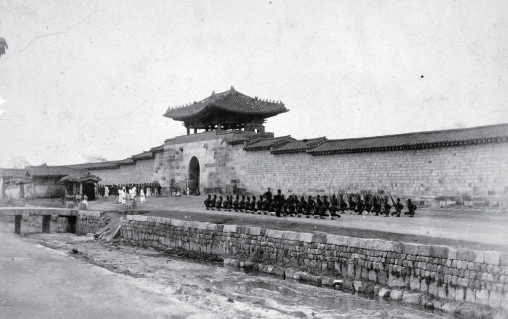

“Soldiers of the Daehan Empire Training Outside the Geonchun Gate of Gyeongbok Palace” Photographer unknown, Undated.

Gelatin silver print, 9.8 x 13.8 cm.

© Independence Hall of Korea

“Dancing Students at Nabawi Cathedral”

Florian Demange, 1900s. Dry glass plate, 10 x 15 cm.

© Jeong Seong-gil

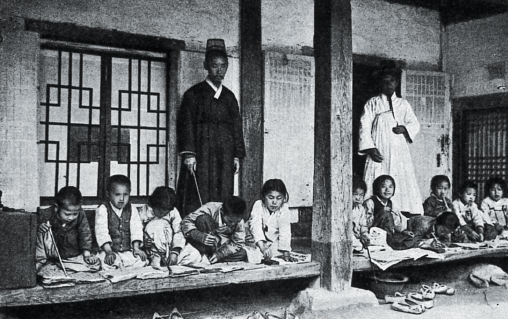

“Gyemyeong School”

Norbert Weber, OSB, 1911. Dry glass plate.

© Benedict Press Waegwan 2012

Though memories may fade with time, photographs remain intact and take us back in time. That’s why people like to say, “All that remains are the photos.” Human desires to leave possessions behind, make a mark in the world and be fondly remembered concur with the characteristics of photographs. One hundred years ago, however, when photographs first arrived in Korea, people were not as well disposed to them as they are now.

The arrival came toward the end of the Joseon Dynasty, when only very few people in the country, such as foreign missionaries, owned a camera. For the vast majority, their first encounter with a camera was a foreigner suddenly pointing the lens of a mysterious black box at them. It was something to be feared. The thought of a person’s appearance being captured and frozen in time was terrifying and ominous. Rumors spread that “having your picture taken will rob you of your soul.”

On the other hand, for the wealthy upper class, photographs were gifts of a new civilization they were lucky enough to possess ahead of their time. Having one’s portrait taken became a symbol of opulence. Indeed, when Korea’s first commercial photo studio, Cheonyeondang (“Natural Studio”), opened in 1907 in Sogong-dong, right in the heart of Seoul, influential figures from the royal court, the wealthy and foreigners beat a path to the door. But another half century would pass before photographs became an everyday fixture among the general public.

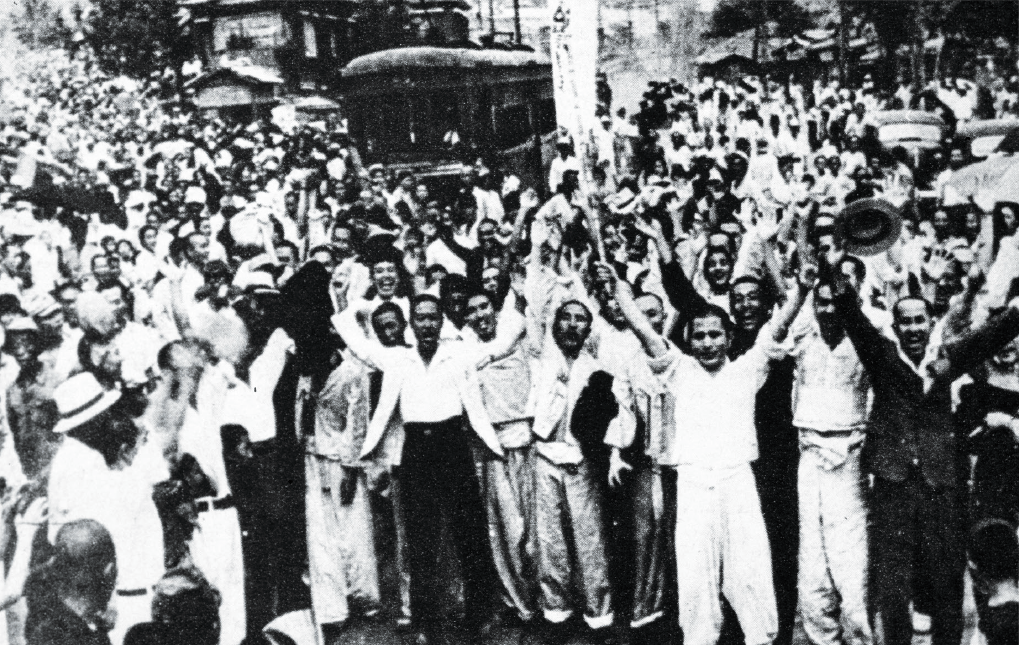

“Patriots Released from Jail upon National Liberation”

Photographer unknown, 1945. 20.3 x 25.4 cm. © Independence Hall of Korea

“Busan”

Choi Min-shik, 1965.

© Choi Yu-do. Photo source: Noonbit Publishing Co.

The First Boom

During the Japanese colonial period (1910-1945), cameras were high-end items, costing as much as an average house in Seoul. As such, it was thought to be the sole property of wealthy dilettantes. It was not until after the Korean War ended in 1953 that commercial photo studios began to appear and cameras spread among professional photographers such as photojournalists and shutter-happy amateurs who could afford them. It was around this time that an epochal event sparked a boom in photography.

In 1957, the art museum in Gyeongbok Palace hosted the international touring exhibition “The Family of Man.” It created quite a stir, attracting some 300,000 visitors. Curated by Edward Steichen, then director of the photography department at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York, the exhibition displayed some 500 works on the theme of humanism, taken by photographers from around the world. The exhibition opened the eyes of Koreans to the role and value of photography as a new art form.

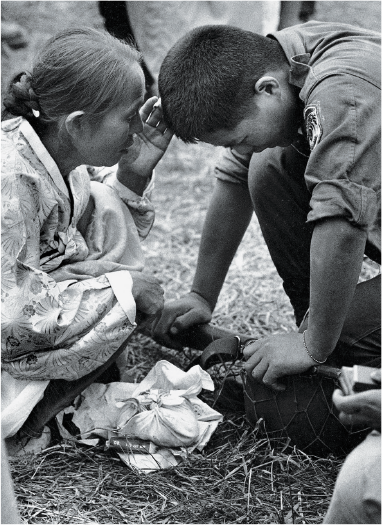

“Soldier Dispatched to Vietnam Speaks with His Mother,

Yeouido Airfield”

Shisei Kuwabara, 1965.

© Shisei Kuwabara. Photo source: Noonbit Publishing Co.

Inspired by the exhibition, Korean daily Dong-A Ilbo launched the Dong-A Photo Competition for the general public in 1963, and in the following year, a photography category was included in the National Art Exhibition. Thanks to the annual state-sponsored exhibition, the general perception of photography gradually began to change. In the same year, Seorabeol Arts University established Korea’s first department of photography at an institution of higher education. The training of professional photographers, distinguished from amateurs, triggered qualitative and quantitative developments in the field.

In the general trend of realism that prevailed during the 1960s and 1970s, many impressive photos focused on the non-elites. They included the “Human” series by Choi Min-shik, who captured the lives of ordinary people; “Holt’s Orphanage,” photos of children of dual ethnic heritage by Joo Myung-duck; “Back Alley Views” by Kim Ki-chan, who recorded the lives of people inhabiting the alleyways of Seoul over 30 years; “Hometown,” a series by Kim Nyung-man that zoomed in on the New Community (Saemaul) Movement and the lives of rural people; and “Yun-mi’s Home,”

biographical photos by Jeon Mong-gag, who recorded his daughter from birth to marriage. Thus, Koreans who were first recorded on film from the perspective of foreigners came to be seen through the lenses of native photographers.

Around this time, it became a trend to hang family photos in the middle of the living room or the main hall of a house, the places where they would be most noticeable. The photos included weddings, parents’ 60th birthday banquets, babies’ 100th day celebrations, or graduates clad in cap and gown. When visitors came, the family album was proudly proffered for them to peruse with tea and snacks. But up until the late 1970s, it wasn’t yet common for most people to stand in front of a camera except on special occasions.

The wariness toward photography receded when decades of military dictatorship ended and a civilian president chosen through a free democratic election was inaugurated in 1993. Therefore, the springtime of democratization can also be called the springtime of photography.

Up Close and Personal

In the 1980s, cameras became consumer items. The decade saw universities rushing to establish photography departments. Soon, over one thousand photography majors graduated annually from some 20 universities. In the mid-1980s, the first generation of photographers who had studied overseas began to return home. This coincided with Korea’s phenomenal economic growth and the subsequent expansion of the advertising industry. As the demand for advertising photos skyrocketed, photo studios catering to the industry began to open one after another in Seoul’s Chungmuro area. This in turn stoked demand for professional photographers, which further multiplied photography departments at universities amid the burgeoning interest of the general public.

Economic growth not only energized the demand for photos to be used in corporate ads, it also bolstered demand from individuals with deep pockets. The most notable example was wedding photography. Using diverse marketing strategies, wedding photography studios set about creating new desires.

Previously, wedding photography meant photos of the wedding itself, but going into the 21st century, it has become customary to take a series of staged pre-wedding photos inside a studio or at scenic spots. These photos help to assuage any discontent left by a wedding ceremony hurriedly conducted at a commercial wedding hall. Apart from the perception that such photos constitute a visual record of one of the most important occasions in one’s life, much of the satisfaction appears to come from dressing up and posing like the prince and princess in a fairy tale, the groom in his tuxedo and the bride in her pure white wedding gown.

Interestingly, the expansion of wedding photography led to a subsequent boom in baby photos. Young couples who had taken special photos of their weddings began to act out their fantasies once again when they started having children. A few decades ago, all that parents did to mark their baby’s 100th day or first birthday was to go to a local photo studio and take a commemorative picture of their child dressed in a traditional hanbok. But in recent times, parents more often than not visit a specialized baby studio to take a series of pictures, like a celebrity photo shoot.

Some parents won’t even wait for the traditional 100th day. Persuaded by successful marketing, they now have their babies photographed on their 50th day of life. Children exposed to cameras at such an early age, from the ultrasound pictures taken while in their mothers’ wombs, are naturally comfortable with the flood of images of the Internet era.

“South and North Hand-in-Hand, Panmunjom”

Kim Nyung-man, 1992. © Kim Nyung-man

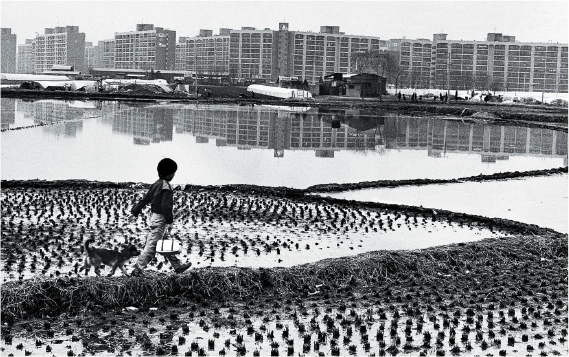

“Lost Scenes 135, Jamsil, Songpa District”

Kim Ki-chan, 1983. © Choe Gyeong-ja. Photo source: Noonbit Publishing Co.

“Jeju Island Rite, East Gimnyeong-ri”

Kim Soo-nam, 1981. © KIMSOONAM PHOTO

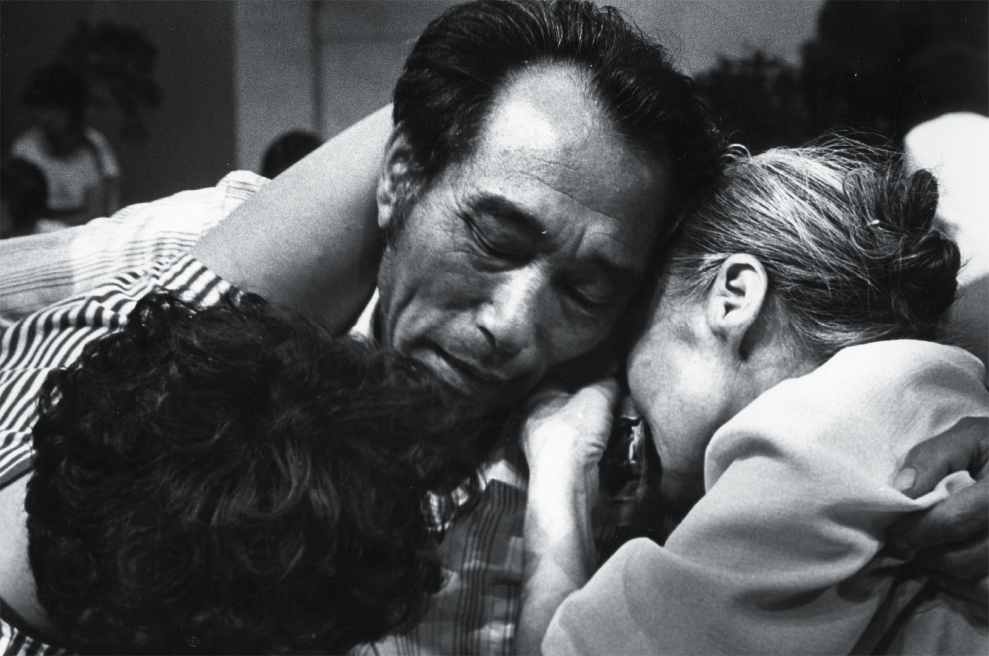

“Family Reunion”

Hong Sun-tae, 1983. © Hong Seong-hui

“Untitled”

From “Yun-mi’s Home,” Kang Woon-gu, 1989.© Kang Woon-gu

“Untitled”

From “Yun-mi’s Home,” Jeon Mong-gag, 1964.© Lee Mun-gang

The trepidation and intimidation once felt when facing a camera has vanished; Koreans now pose with poise and confidence. It brings home the fact that in diverging from written and spoken language, they have learned to enjoy the freedom of visual language.

Darker Image

In the early days of photography in Korea, avoidance of cameras was largely borne out of ignorance. Except for the aforementioned special occasions, the aversion continued through the 20th century in certain parts of Korean society. Trepidation stemming from constant national upheaval replaced the initial misguided beliefs about soul-robbing. Scars from the Korean War, post-war political turmoil, and a sense of victimization in resistance to military dictatorship and struggle for democratization - all cast suspicion toward photography.

Anti-communist ideology due to national division dominated South Korean society in the second half of the 20th century. Military dictators took advantage of anti-communism to perpetuate surveillance and cracked down on democratization advocates, creating a social atmosphere of oppression, insecurity and terror. In an environment in which one’s life could be turned around in an instant by stepping forward at an inopportune time, people were guided by the notion that one must avoid sticking out in a crowd; anonymity was deemed essential for survival. Thus, the evidence-collecting function of photography unnerved people when confronted by a stranger’s camera in public places.

The wariness toward photography receded when decades of military dictatorship ended and a civilian president chosen through a free democratic election was inaugurated in 1993. Therefore, the springtime of democratization can also be called the springtime of photography. In some respects, though, wariness toward photography persists. The North-South division of the Korean nation prevents caution from completely dissipating.

A couple pose during their wedding photo session. Unlike in the early 1990s, when a wedding photography boom began and most couples had their pre-wedding photos shot at outdoor locations, the preference these days are photos taken in a studio in the manner of a fashion shoot. © Vienna Studio

A Shutterbug Nation

Nevertheless, an age when everyone is a photographer has arrived. Cameras, once high-end luxury goods, have entered every home, be it in the form of high-resolution camera phones or DSLR (digital single-lens reflex) cameras. One may say that everyone now has a camera. Photography, as a visual language, has become a medium replacing written and spoken language. On the back of Internet technology, a new generation more comfortable with images than writing has emerged.

Around 10 years ago, a newspaper article, citing a survey, said that the most popular prospective husbands were photography majors. The reasons cited were that most photography students at universities come from rich families; that photographers travel a lot; and that photography work allows control of one’s own time.

Around the same time, a professor of photography told me an interesting story. In 1979, when he said he was going to the United States to study photography, people asked, “All you have to do is press the button.

A baby girl is dressed like a magazine model for a photo session in a studio. While parents in the past marked their baby’s 100th day or first birthday by simply having a commemorative picture taken of their child dressed in a traditional hanbok at a local photo studio, many young parents these days celebrate the 50th day or 200th day as well by taking their child to a photo studio that specializes in baby pictures. © Sarangbi Studio

Why do you need to go all the way there to America to study photography?” Now those same people marvel at his foresight.

Photography is proliferating rapidly; the number of amateur photographers is said to be several million with hundreds of photo contests around the country stimulating their enthusiasm. Prize winners are awarded points, which are compiled to qualify for entry into the Photo Artists Society of Korea, which now has some 10,000 members. Photography is also a popular hobby, like hiking or fishing, for many retired people.

At this very moment, countless people in all parts of the country are probably taking pictures of something. Surely, this is one sign that Korean people, suppressed for nearly a century while experiencing colonial rule, war and national division, and military dictatorship, have now found freedom and enjoyment in life. The trepidation and intimidation once felt when facing a camera has vanished; Koreans now pose with poise and confidence. It brings home the fact that in diverging from written and spoken language, they have learned to enjoy the freedom of visual language.

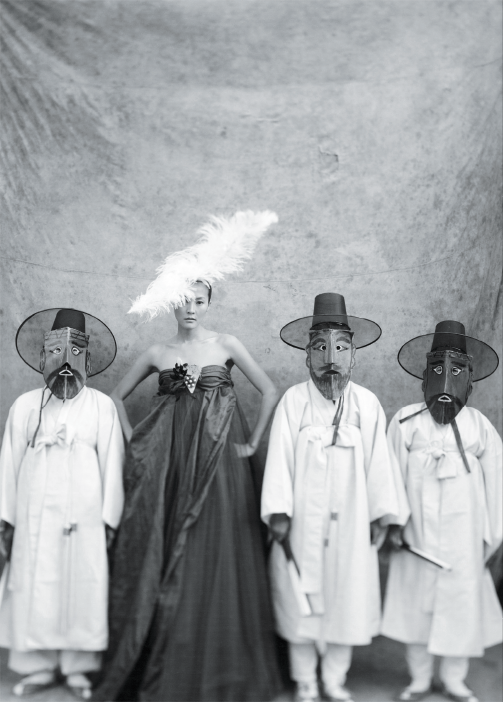

“Beauty and the Beast”

Koo Bohn-chang.

From VOGUE Korea, December 2002.

“DMZ”

Park Jong-woo, 2017.

“Red House I #007, 2005,

Pyongyang”

Noh Sun-tag, 2005.

The Seoul Plaza in frontof the city hall is packed with “Red Devils” cheering

for their national team playing against Spain in a Korea/Japan World Cup

quarterfinal, on June 22,

2002.© Chosun Ilbo

Citizens protest President Park Geun-hye’s misrule in a massive candlelight rally,

held at the Gwanghwamun Square in central Seoul,on November 19, 2016.

© Yonhap News Agency