The essence of photography lies in its ability to capture moments in time and history. True to this principle, Korean documentary photographers have served as witnesses to the country’s tumultuous history. It may be said that modern Korean photography was born in 1945 when the nation was liberated from Japanese occupation. Over time, photographs obtained the power to turn the tide of history.

The birth of modern Korean photography overlapped with the nation’s liberation from Japanese rule on August 15, 1945. Under the suppression and surveillance of colonizers, Korean photographers had mostly been confined to taking landscape pictures. Now, however, they were able to capture their country and fellow compatriots from their own perspectives. In that sense, the nation’s liberation day can also be deemed the “independence day” of Korean photography.

Unlike paintings, where images can be rendered on canvas from memory, one has to be at the scene to take a photograph. Many photographers voiced their opinions through pictures capturing historical events they personally witnessed. Among them was Lee Kyung-mo (1926-2001), then a 19-year-old photographer from Gwangyang in South Jeolla Province.

Lee’s first camera was a gift from his grandfather. Originally, he dreamed of becoming an artist, but when he received a Minolta Vest as he started middle school, he embarked on a lifelong pursuit of photography. On the day of the country’s liberation, he hit the streets with his camera and captured images of the throngs of people overwhelmed with joy. It was at that very moment that modern Korean photography was born.

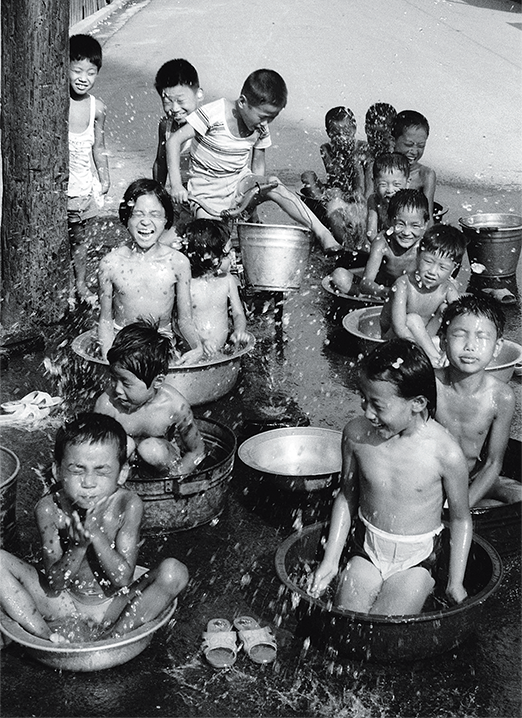

“Children Playing in the Alleyway Haengchon-dong, Seoul”

Kim Ki-chan, 1972. © Choi Gyeong-ja. Photo source: Noonbit Publishing Co.

From Liberation to Division

Soon afterward, in early September 1945, Lee stumbled upon a strange sight at the entrance of Myeong-dong in downtown Seoul. Instead of Japanese military police, he saw American soldiers roaming around the department store or riding rickshaws. The three years of American military occupation represented a period of further turmoil as Korean society was embroiled in an ideological conflict that eventually led to national division. Many wondered whether it foreboded another era of foreign domination. To a young photographer, it seemed odd to regain independence from the Japanese, only to be placed under American military rule. Lee left many photographs chronicling those times, from the Yeosu-Suncheon Rebellion in South Jeolla Province, sparked by left-right confrontation in October 1948, to the Korean War, which broke out in June 1950.

The short-lived joy of liberation gave way to the pain of division. Some photographers chose to focus their lenses on this somber reality. Han Chi-gyu (1929-2016), a photographer and military intelligence officer, recorded images of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) dividing South and North Korea that was off-limits to civilians.

Han fled to South Korea from the North on a fishing boat and served in the Korean Army during the war. Wherever he went, he always took along his camera. Until he was discharged as a colonel in 1979, he took pictures whenever he visited the DMZ or his subordinate units. During home visits in Seoul, he used his camera to record the changing cityscape and his children growing up. Han’s collection of photographs, published shortly before he passed away, allows us to reflect on the wounds of a divided nation and the military culture that shaped the lives of Koreans at that time.

Plight of the Disadvantaged

South Korea made a miraculous recovery from the ashes of war and territorial division to achieve unprecedented economic growth. Korean documentary photographers turned their lenses toward those left behind amid the rapid industrial development. Among those photographers who chose to document the lives of marginalized people was Choi Min-shik (1928-2013). Having graduated from the Department of Design at Chubi Central Art School in Tokyo in 1957, Choi taught himself photography and began taking pictures of people. Throughout his career, he published a total of 14 photo books that form his “Human” series, portraying the suffering of disadvantaged people, laying bare the human soul and nature.

“I focused my lens on the lives of the less fortunate struggling on the fringes of society. For five decades, my subjects have been those living in poverty and deprivation. No matter how often I pressed the shutter, there was never a single moment in which I doubted their integrity as human beings,” Choi wrote in one of his books.

Having struggled with poverty himself throughout his life, Choi did not regard the poor as mere subjects; he held deep affection for his destitute neighbors and sought to vividly record images of those pushed aside in the race for economic development.

There was another photographer who saw that industrialization and economic growth did not necessarily bring happiness. Kim Ki-chan (1938-2005), who had previously worked at a television network, used to sling his camera over his shoulder every weekend and head to the hillside shantytowns in Seoul. “The alleyway in Jungnim-dong was my spiritual home. When I first set foot there, the boisterous atmosphere brought back memories of the alley in Sajik-dong from my childhood. It was then that I decided that the views of those alleys and the joys and sorrows of the residents would become the lifelong theme of my works,” Kim once recalled.

Kim published six photo books under the theme “back alley views,” as well as a collection of photographs that captured the images of rural people who came to live in Seoul and camped out in front of Seoul Station, and the changing landscape of the farming villages they had left behind. Over decades, he documented the scenes of the narrow alleyways and the lives of their residents, developing an intimacy with his subjects, while his works continued to be reappraised. More often than not, the cost of the country’s relentless push for economic growth was the loss of ties to family, neighbors and hometown. But Kim’s heartwarming images of people living in the back alleys, encouraging and comforting one another through thick and thin, remain an invaluable testimony to this remarkable period in modern Korean history.

After the death of former president Park Chung-hee, who had launched a series of economic development plans during his prolonged iron-fisted rule, Korean society was swept up in the fever for democratization. Students took to the streets in protest against the military dictatorship, and other citizens, who had been sitting on the sidelines, soon joined in. But with the government’s tight control over the media, the public had no way of learning the full truth about the democratization movement or what the ruling elites were plotting. However, despite the clampdown on the media, people became aware of the violent acts committed by the authoritarian regime, particularly the tragic circumstances of the civil uprising in Gwangju on May 18, 1980. And so they stood together at the forefront of the pro-democracy movement.

“American Soldiers Riding Rickshaws, Myeong-dong, Seoul”

Lee Kyung-mo, 1945.

© Lee Seung-jun. Photo source:

Noonbit Publishing Co.

Struggle for Democracy

Kwon Joo-hoon (born 1943), a photojournalist who worked at several news outlets before retiring from private news agency Newsis in 2015, documented major historical events throughout his career of 47 years. At 2 p.m. on May 20, 1986, he was covering the May Day Festival at Acropolis Square of Seoul National University. The theme of the event was “Historical Reevaluation of the Gwangju Uprising,” and Moon Ik-hwan (1918-1994), a pastor and famous anti-government activist, was speaking in front of the students. Suddenly, a student on the rooftop of the student union building shouted a rallying cry, poured thinner all over his body and set himself on fire. Then he jumped, falling seven meters onto a balustrade on the second floor. Other students rushed to him and tried to smother the fire, but to no avail. The flames were finally put out with a car fire extinguisher, but the student, identified as Lee Dong-su, died shortly after being taken to hospital.

Under martial law, no domestic media outlet was brave enough to publish a picture of the shocking scene.

“Korean Soldiers Patrolling the Military Demarcation Line”

Han Chi-gyu, 1972.

© Han Seung-won. Photo source:

Noonbit Publishing Co.

The Hankook Ilbo, which Kwon was working for, was the only newspaper that reported the incident, though in a small boxed article two days later. It was only after the picture was published by the international press that the incident became widely known in Korea. The horrendous scene of a young man diving to his death with his whole body on fire was a stark statement of how desperately students yearned for democracy. Later, a young journalist recalled how the photo had prompted him to change his career path from judge, hoping to deliver the truth to the public.

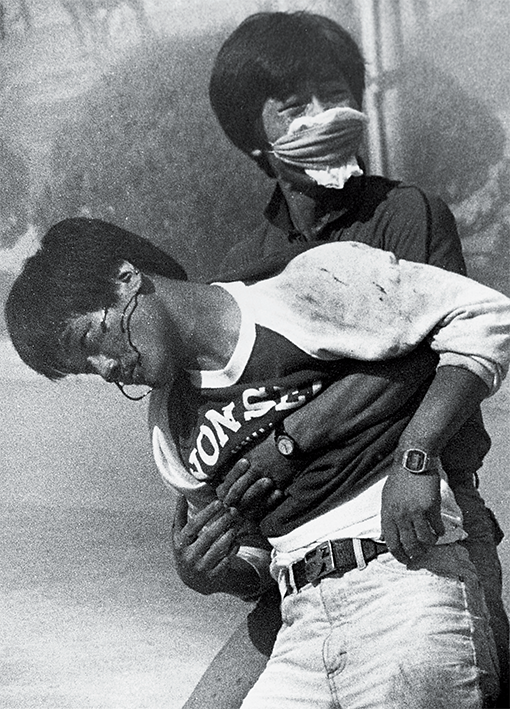

Kwon wasn’t the only photojournalist who chronicled the escalating clash between the authoritarian regime and the pro-democracy camp. Tony Chung (aka Chung Tae-won, born 1939), who was the head photographer at Reuters Korea, captured scenes of the Gwangju Uprising in 1980 and the June Democracy Movement in 1987 that were circulated worldwide. It was Chung’s photograph of Lee Han-yeol, a Yonsei University student, fatally injured by a tear gas grenade during a demonstration in front of his school on June 9, 1987, which became the catalyst for the June Democracy Movement and an eternal symbol of the Korean people’s struggle for democracy.

“Collapsing Lee Han-yeol”

Chung Tae-won, 1987.© Chung Tae-won. Photo source: Noonbit Publishing Co.

Pictures of Lee, knocked unconscious with blood running down his face, spoke of the government forces’ brutality, igniting rage among the general public.

Chung recalled that as he noticed the student, collapsing amid tear gas just as he was about to raise his hand to the back of his head, he immediately rushed towards him. He took a close-up shot of a fellow student trying to help him up. Intuitively knowing that this was big, Chung headed straight to his office, developed the photo in the darkroom and transmitted it worldwide.

Then he managed to get a hold of the doctor who had initially treated the student and inquired about his condition. He was told that the student was in a coma and wasn’t going to survive. Lee Han-yeol never regained consciousness and died on July 5. Whenever he covered street protests, Chung always stood at the side of the student demonstrators and took close-up shots. During the civil uprising in Gwangju, he stood among the civilian militia and captured vivid scenes of the bloody clashes with bullets flying in all directions.

Photographers have thus been witnesses to epochal moments in modern Korean history. With their cameras, they eloquently accused military dictatorships and empathized with those who lagged behind in the march toward industrialization. Documentary photographers revived what government censorship could have obliterated from our memories, public records, and history. Through their photographs, they have sought to embrace the weak rather than the strong, victims rather than perpetrators, losers rather than winners, and democracy rather than power.

Photographers have been witnesses to epochal moments in modern Korean history. With their cameras, they eloquently accused military dictatorships and empathized with those who lagged behind in the march toward industrialization.

Democratization of Photography

Critical moments in Korea’s contemporary history since 1945, marked by a vortex of change and the frenetic pace of political, economic and social development, have been chronicled mainly by professional photojournalists. However, the “candlelight revolution” that began in October 2016 showed how times have changed, as ordinary citizens participating in the rallies all became documentary photographers.

Earlier, on April 16, 2014, young students trapped inside the sinking Sewol ferry on a school trip recorded their last desperate moments with their cellphones. The heartrending photos and videos caused deep grief among the public and served as crucial evidence of the tragic incident - how hundreds of students met their death as the capsized ferry was virtually abandoned without appropriate rescue efforts by the concerned authorities.

In the days of analog photography, photojournalists packed their equipment and carried it to the scenes of accidents and incidents. But in the digital age, anyone at the scene, even without professional expertise or equipment, can take pictures from their own perspective thanks to high-quality smartphone cameras. In this sense, one could say that photography has also become “democratized.”

During the candlelight rallies at Gwanghwamun Square in downtown Seoul, which continued through the winter of 2016, protesters taking selfies with their families or friends were a common sight. The countless snapshots they took there will forever remind them of the day they joined the act of defiance against a scandal-tainted president with a burning passion for democracy.