Situated in the heart of Seoul, Jeongdong (a.k.a. Jeong-dong) was the birthplace of the Korean Empire and the first home of Western legations, Christian missionaries and technical advisers. The enclave became a showcase of Western modernization that the Korean emperor sought to emulate. However, Japan’s imperialist encroachment crushed his dreams of creating a strong independent state. The empire ended in 1910 after only 13 years.

The throne hall of Deoksu Palace is surrounded by traditional palace halls and Western-style buildings erected in the early 20th century. In 1897, Gojong, the 26th monarch of the Joseon Dynasty, proclaimed the Korean Empire at this palace and carried out active diplomacy, but in 1910 the nation lost its sovereignty. © Deoksugung Palace Management Office

Korea opened its doors to the West in the 1880s and Jeongdong changed forever. Traditionally, the nobility and courtiers had planted themselves in the neighborhoods close to the king at Gyeong-bok Palace. Likewise, envoys from Western countries gravitated to Jeongdong, eager to set up connections with the royal court.

American Lucius Harwood Foote arrived first. In 1882, Korea and the United States signed their Treaty of Peace, Amity, Commerce and Navigation (a.k.a. Shufeldt Treaty), and Washington dispatched Foote to establish an American legation. He did so by purchasing a newly-built home in Jeongdong from an aristocratic family in 1884. British, Russian and French counterparts soon followed. They constructed lavish Western-style buildings that projected their wealth and power, unlike Foote’s humble purchase, a traditional Korean house.

Transformed into a hive of diplomatic activity, Jeongdong became known as the “Legation Quarter” or “Legation Street.” Hotels and shops soon began to appear to cater to the diplomatic corps and their visitors. Indeed, most foreigners moving to Seoul settled in Jeongdong, reshaping its character.

The new arrivals included Christian missionaries. Next door to the U.S. Legation, the headquarters of the U.S. Presbyterian Church and Methodist Church appeared, soon to be followed by modern hospitals and missionary schools such as Pai Chai Hakdang, Ewha Haktang and Kyungshin School, forerunners of prestigious schools today. Especially noteworthy was the missionaries’ concerted effort to educate girls at a time when the Korean school system excluded them. For Koreans, the neighborhood represented all that was modern and Western.

In 1897, King Gojong proclaimed the founding of the Korean Empire (Daehan Jeguk). The declaration recast Korea as an independent state under international law, thus severing the nation’s centuries-old tributary relationship with China. It also ended the Joseon Dynasty, which had ruled Korea since 1392 and fallen into irreparable decay. The 45-year-old king named the era “Gwangmu,” literally “shining warrior,” and changed his title to Gwangmu Emperor. He hoped the new dynasty would lead to a prosperous and modernized state that would vanquish Chinese, Japanese and Russian pressure on Korea’s sovereignty.

King Yeongchin (center, front row), the last crown prince of Joseon, poses with high-ranking officials at Seokjojeon (Hall of Stone) in this photo dated 1911. The neo-classical building was where Emperor Gojong received foreign envoys. It was turned into an art museum after Japan’s annexation of Korea. © National Palace Museum of Korea

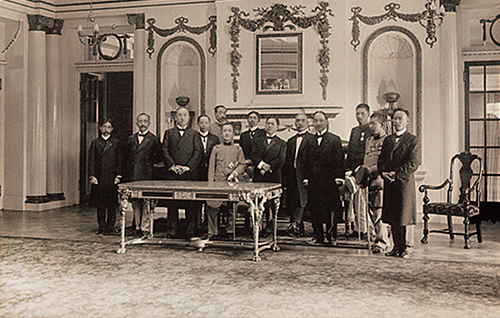

Foreign heads of mission in Hanseong (old name of Seoul) pose in this photo taken in 1903 after a meeting at the U.S. Legation at the invitation of Minister Horace N. Allen (fourth from right). The U.S. Legation was the first foreign legation set up in Jeongdong.

Reshaping the State

Gojong also decided to remodel Gyeongun Palace in Jeongdong into a new imperial palace. Styling himself as an enlightened ruler, he enthusiastically promoted Western architecture to make his palace an expression of his resolve to modernize the country. The Korean-style throne hall, Junghwajeon (Hall of Central Harmony), remained a symbol of traditional authority, and newly constructed Western-style buildings represented the country’s modern transformation.

Among the new buildings was Jungmyeongjeon (Hall of Grand Light), built on the rear side of the palace grounds adjacent to the U.S. Legation. Originally a Western-style, single-story building that served as the royal library, it was rebuilt twice as a double-story brick structure because of fires, ultimately becoming the emperor’s living quarters after 1904. In September 1905, on the second floor of this building, Emperor Gojong met Alice Roosevelt, daughter of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt. She and Secretary of War William Howard Taft were leading a large diplomatic entourage through Asia and the emperor sought U.S. support for the Korean Empire. He extended the greatest hospitality on the occasion and afterwards presented Alice Roosevelt with a photo of himself, taken in the hallway of this building. However, when the entourage visited Tokyo, Taft did not oppose Japan’s assertion that turning Korea into a Japanese protectorate would stabilize East Asia.

The help from world powers that Emperor Gojong counted on when he relocated the imperial palace to Jeongdong and focused on diplomacy never materialized.

A photo of Emperor Gojong from “Photo Album of the Yi Royal Family,” published in 1920. The photo shows the emperor with his hair cut short, removing his topknot, after his forced abdication and the ascension of his son, Sunjong, to the throne in 1907. © Seoul Museum of History

Another two-story addition was Dondeokjeon (Hall of Promoting Virtue). It was constructed in 1901 to receive foreign guests at a ceremony being planned to commemorate Emperor Gojong’s 40th jubilee. The ceremony was cancelled, but the building combining Gothic and Renaissance styles was frequently used for meetings between the emperor and foreign dignitaries and banquets attended by his high officials dressed in tailcoats.

Seokjojeon (Hall of Stone) is the biggest Western-style structure remaining at the palace. Two Britons were instrumental in its construction. John McLeavy Brown, who served as the emperor’s financial adviser, proposed the building, and J. R. Harding, an engineer who had worked in Shanghai, was commissioned to design it. He produced a grand, neo-classical building. Although the palace coffers were very low, Emperor Gojong had high hopes the building would become a symbol of the country’s modernism. After 10 years of construction, the building was completed in June 1910, two months before Japan’s annexation of Korea.

The Korean Empire also embarked on other major development projects. Intellectuals and officials had become increasingly aware of the modernization that was underway in other countries, realizing that Korea was a latecomer to the Industrial Revolution. Yi Chae-yeon, chief magistrate of Hanseong (old name for Seoul), who had served at the Korean Legation in Washington, D.C., drew up a master plan for urban development, using the U.S. capital as a model.

Hanseong Electric Co., which was established with Emperor Gojong’s private funds, undertook basic infrastructure projects such as an electric grid, telephone lines and waterworks as well as a tram service.

The first tramline, running some 8 kilometers from Seodaemun in the west to Cheongnyangni in the east, opened in 1899. It was the second tramline in Asia after that in Kyoto, Japan. Then, in 1900, street lamps were installed along Jongno, one of the main thoroughfares of the city, lighting up the night.

Diplomatic Endeavors

From the time he began pursuing enlightenment policies in the 1880s, Gojong was eager to graft elements of Western civilization and receive information from missionaries, diplomats and travelers. He introduced the telephone and electricity to the palace and took pleasure in Western habits such as drinking coffee and champagne. When he met foreign envoys, he wore his Prussian-style uniform, and he hosted Western-style banquets and formal French dinner parties.

To take charge of entertaining foreign guests at the palace, Emperor Gojong hired Antoinette Sontag, the sister-in-law of Karl Waeber, the first Russian consul-general to Korea. On the land that the emperor granted her, the Russian woman of German origin built and operated the Sontag Hotel. To pursue his modernization policies, the emperor also hired some 200 foreigners to serve as advisers to the government ministries and as technicians for his infrastructure and transportation projects. The foreign consultants introduced Western systems but in a way that advanced the interests of their own countries. Many of them lived in Jeongdong as neighbors of the missionaries and diplomats, adding a new blend to the early foreign community in Seoul.

The Korean Empire mounted a determined effort to become a member of the international community, and the Jeongdong area, both officially and unofficially, became the center of diplomatic activities. After posting its first resident diplomat to Washington, D.C. in 1887, the Korean Empire dispatched ministers extraordinary and plenipotentiary to Russia, France, England and Germany, and established legations in those countries. Moreover, Emperor Gojong sent a close aide, Min Yeong-hwan, as special envoy to the coronation ceremony of Nikolai II of Russia in 1896, as well as to the commemoration ceremony for the 60th jubilee of Britain’s Queen Victoria in 1897.

As for international conventions, the Korean Empire became a member country of the Universal Postal Union in 1899 and a signatory to the Geneva Convention in 1903. However, it was left in the cold at the first Hague Peace Conference in 1899, a gathering of representatives of 26 member nations to seek peaceful solutions to international conflicts. In 1902, the Korean Empire submitted a membership application to prepare to fight Japan’s infringement on its sovereignty.

Shortly before the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904, the Korean Empire sent letters to major world powers declaring its neutrality through an envoy dispatched to Zhifu, China, in an attempt to avoid the incessant Japanese surveillance of its diplomatic activities. Two Europeans purportedly helped palace officials draft the statement of neutrality - Emile Martel, the French tutor to the royal household, and a Belgian adviser - under the direction of Yi Yong-ik, a close and devoted aide to Gojong. Vicomte de Fontenay, acting minister at the French Legation, translated the statement into French, which was then telegraphed by the French vice-consul in Zhifu. However, the effort was in vain. As Japan waged war on Russia, it sent thousands of troops into Korea, beginning its illegal military occupation of the country.

Jungmyeongjeon (Hall of Grand Light) was built in 1899 as the imperial library but from 1904 it served as Emperor Gojong’s office and living quarters. The Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty of 1905 was signed here. It currently stands outside the western walls of Deoksu Palace.

A photo of Jungmyeongjeon from “History of Deoksu Palace,” a book written by Japanese colonial historiographer Oda Shogo and published in 1938. The hall went through major renovations after a fire in 1925. © Korea Creative Content Agency

Robbed of Sovereignty

The international community turned a blind eye to Japan’s blatant violation of international law. In fact, Japan received the support of Britain and the United States through the second Anglo-Japanese Alliance and the so-called Taft-Katsura Agreement, which safeguarded the respective countries’ interests in China and Korea. U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt brokered a peace deal between Russia and Japan, and subsequently became the first American to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The agreement did not address the Japanese presence in Korea. Thus, the United States, Britain and Russia effectively recognized Japan’s claimed rights over the Korean Empire.

In 1905, fresh from its defeat of Russia and becoming a new global power, Japan forced the Korean Empire to sign a protectorate treaty. Emperor Gojong refused to sign it to the very end, but threatened by Ito Hirobumi, five out of Korea’s eight cabinet ministers finally signed the treaty. Under international law, the treaty was invalid because it was signed under force. Nonetheless, Japan rushed to announce the treaty to the world and made the Korean Empire its protectorate.

The United States was the first country to close down its legation in Korea. When other foreign powers heard the news, they too did not hesitate to withdraw. France, a military ally of Russia, was the last to close its doors. The help from world powers that Emperor Gojong counted on when he relocated the imperial palace to Jeongdong and focused on diplomacy never materialized. He had to face the bitter reality that the powerful, advanced nations would not always protect the independence and sovereignty of weaker nations.

Undaunted, Emperor Gojong continued his efforts to persuade the international community. With the help of Horace N. Allen, a medical doctor and missionary who had served as the U.S. minister to Korea, Gojong requested American intervention in affairs on the Korean peninsula, but there was no answer. Then, through Homer B. Hulbert, an American missionary and educator newly posted to Korea, he tried to send hand-written letters to Austria, Belgium, Britain, China, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Russia and the United States, but their heads of state did not want to become involved with Japan’s territorial ambitions. In short, his argument that the Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty of 1905 was invalid under international law because it was signed under duress was ignored. He also attempted in vain to launch an appeal at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague.

In a last-ditch effort, Emperor Gojong decided to dispatch three close aides - Yi Sang-seol, Yi Wi-jong and Yi Jun - to the second Hague Peace Conference, where representatives from 44 countries convened from June to October 1907. The mission was unannounced and the secret emissaries slipped into Russia to make their way to The Hague. But they were blocked from the conference and had to convey their plea for international intervention through journalists from around the world reporting on the conference. However, the world powers again ignored the Korean Empire’s plight.

To reprimand Emperor Gojong for the secret mission, Japan forced him to step down from the throne in July 1907. His unwilling abdication in favor of the crown prince, later known as Sunjong, took place at Jungmyeongjeon. The new emperor was moved to Changdeok Palace and the abdicated emperor remained at Gyeongun Palace, where he lived in confinement until he passed away on January 21, 1919. Japanese agents were suspected of having poisoned him, and five weeks later, the March First Movement erupted, one of the earliest displays of massive public resistance in Asia against colonial occupation.

The winding byway along the stone walls of Deoksu Palace has a special, quiet ambience in the middle of bustling Seoul. The left side shows the wall around the palace’s rear compound while the right side shows the U.S. ambassador’s residence. © Getty Images

The Passing of the Emperor

Bereft of its owner, Gyeongun Palace, now renamed Deoksu Palace, underwent systematic dismantling. Japan drastically reduced the size of the palace grounds and razed many halls. Jungmyeongjeon, where Gojong had resided, was leased to foreigners as a social club. Dondeokjeon, which had been built for the reception of foreign guests, was demolished and replaced with a children’s park. During the 1930s, Japan removed many more structures to create space for a public park. With the sovereignty and dignity of the Korean Empire ruthlessly destroyed, the Jeongdong era came to an end in 1910 when Japan formally annexed Korea.

Today, the American missionary Homer B. Hulbert, who assisted Emperor Gojong’s desperate search for international support, is remembered as a man who remained Korea’s friend to the end. He is buried at the Yanghwajin Foreign Missionary Cemetery in Seoul. Jeongdong has become a cozy pocket of solitude amid the cacophony swirling around the Seoul City Hall across the street. The remaining palace structures of the short-lived empire summon history and architecture buffs. Jeongdong-gil, the area’s narrow winding cobblestone street shaded by ginkgo trees and flanked by the palace wall, beckons pedestrians to make a detour into another era.

Tapgol Park: Springboard for Independence

A century ago, Seoul’s first public park was a hotbed of political dissidence. It became the springboard of the March First Movement against Japanese colonial rule, a major milestone in Korea’s struggle for sovereignty and democratic republicanism.

A scene from the funeral procession of Emperor Gojong, who passed away on January 21, 1919. As the rumor spread that he had been poisoned by Japanese agents, his death ignited the March First Movement, a nonviolent struggle to regain independence from Japanese rule.

A commemorative photo of the Korean Empire Military Band with Franz Eckert (center in the front row, wearing a fedora) after a performance at the octagonal pavilion of Tapgol Park in 1902. © Korea Creative Content Agency

Nestled in central Seoul, Tapgol Park became a podium for disgruntled citizens in the late 19th century. Indeed, social reforms had given a voice to everyone, even butchers, outcasts of traditional Korean society. After airing their grievances and desires, orators underscored their fervor by marching to the nearby front gate of Gyeongun Palace to submit written appeals. All of that ended when Japan forcibly colonized and annexed Korea between 1905 and 1910.

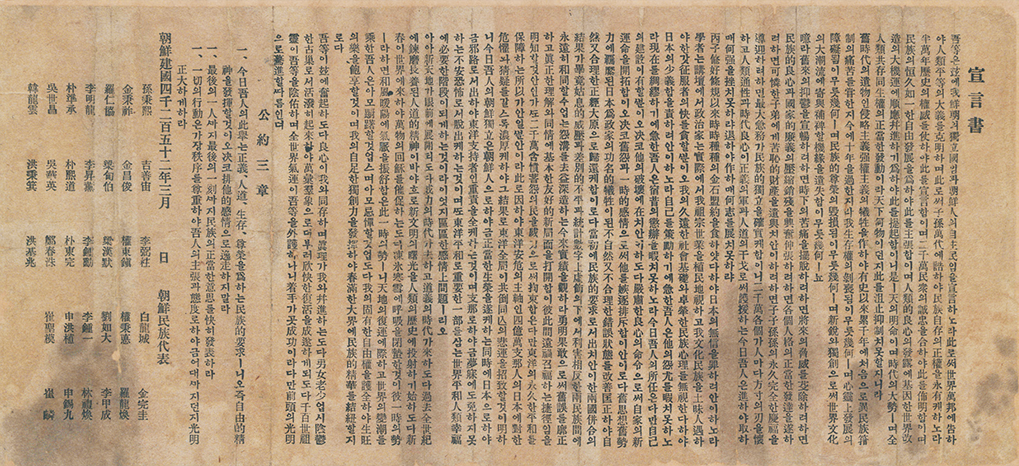

By 1919, pent-up resistance to Japan’s de facto military rule of Korea reached boiling point. On March 1, the Korean Declaration of Independence, largely the work of student activists, had its first public reading at Tapgol Park. Nationwide demonstrations ensued. Although they were nonviolent, the Japanese military reacted with mass arrests and killings that quashed the dissent after two months. Nevertheless, the movement sowed seeds for a Korean provisional government and inspired people’s movements in other Asian countries under colonial occupation.

King Gojong envisioned a public park as part of his urban reform campaign which began in 1896. His financial adviser, Northern Irishman John McLeavy Brown, turned the nearly two-hectare site of the former Wongak Temple into Seoul’s first Western-style park around the turn of the century. The compact venue, surrounded by simple homes, was called Pagoda Park, in recognition of the temple’s 10-tier marble pagoda, later designated as National Treasure No. 2, which still stands at the park today. In 1991, the site officially became Tapgol Park; tapgol means “village with a pagoda.”

Open Space for the Public

As part of the preparations to mark the 40th year of Emperor Gojong's reign, an octagonal pavilion was installed in the park in 1902. The park accommodated the first public concert by a Western-style orchestra in Korea, and it was also where the Korean Declaration of Independence was first heard publicly on March 1, 1919.

German composer Franz Eckert formed the orchestra at the invitation of the Korean Empire, having previously performed similar tasks in Japan. Eckert arrived in Seoul in early 1901 and formed an orchestra of military musicians capable of playing Western instruments. They regularly played Western music in the park for the foreign community that populated the Jongno district, which surrounded the park.

The next year, Eckert composed the national anthem of the Korean Empire, or “Daehan Jeguk Aegukga.” Featuring a Western music scale and rhythm with Korean lyrics, it was played for the first time on September 9, 1902, during the birthday celebrations for Emperor Gojong. The anthem was performed on national holidays, at events of the imperial court, and at schools of all levels. Along with the national flag, named Taegeukgi, the anthem served to inspire patriotism. For his efforts, Eckert was awarded the Taegeuk Medal of the Korean Empire and upon his death in 1916, he was buried at the Yanghwajin Foreign Missionary Cemetery in Seoul.

The anthem featured the lyrics, “May God help our emperor to exert his authority over the world for a long time to come.” When Japan annexed Korea in 1910, it was banned and replaced by the Japanese national anthem that Eckert had arranged in 1880. But among the independence fighters who took refuge around the world in places such as Hawaii, Russia and China, the Korean Empire’s anthem continued to be sung, albeit with slightly altered lyrics and tune in each place.

The Declaration of Independence is a statement signed by 33 representatives of the Korean people proclaiming independence from Japanese rule. The statement was read at midday on March 1, 1919, at Tapgol Park, sparking nationwide protests against Japan. © Independence Hall of Korea

Prelude to Royal Funeral

On January 21, 1919, Emperor Gojong suddenly passed away at the age of 67. In the preceding years, he had been forced to abdicate and held in confinement at Deoksu (formerly Gyeongun) Palace by the Japanese colonial government. Rumors that the Japanese colonizers poisoned him circulated widely and gained acceptance. Mourners from all over the country gathered in Seoul for the funeral, which was scheduled for March 3.

On March 1, the rehearsal day for moving the funeral bier, Han Wi-geon, a student at Gyeongseong Medical School, walked up to the platform in the octagonal pavilion at Tapgol Park and as student representative read aloud the Declaration of Independence. Thousands of college and secondary school students from public and private schools took to the streets to demonstrate against the Japanese. The crowd of mourners who had gathered at the front gate of Deoksu Palace joined the students and together they shouted “Daehan dongnip manse,” which means “Long live Korea’s independence!”

This marked the beginning of the March First Movement, also known as the Samil (March 1) Manse Movement. It was the biggest and most formidable protest against the Japanese occupation. Originally planned and led by political refugees and students living overseas, religious leaders and other intellectuals, the movement became a mass public outpouring by student protestors and members of the general public.

A new page in history was hence written at Tapgol Park. Ordinary people, freed from the yoke of a class society and taking their first steps toward becoming modern citizens, had gathered to protest against Japanese rule and demand their country’s independence. In April 1919, as a result of this movement, the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea was established in Shanghai, China. It enacted a constitution for democratic republicanism, a cornerstone for the new Republic of Korea in 1948.

Gunsan and Colonial Modernization

During the colonial period, Japan used Gunsan to ship rice produced in the Honam region, the granary of Korea. Accordingly, the port city became the victim of Japanese economic exploitation, but paradoxically a symbol of modernization as well.

Gunsan was a natural choice for outbound rice shipments. The port sits on the bank of the Geum River, slightly upstream from its exit into the Yellow Sea, and fertile fields sprawl along the course of a beautiful tributary. Export of Korean rice to Japan began in the Joseon Dynasty under the Ganghwa Treaty (also called the Japan-Korea Treaty) of 1876, the first of a number of unequal treaties Korea was forced to sign. The treaty enabled unlimited, duty-free outflow of rice and other grains. The Joseon government, belatedly realizing the seriousness of the situation, managed to revise the treaty to ban grain exports but Japan continued to raise objections and demand compensation.

Over the 30-year period between the opening of Korean ports under the treaty and the start of the colonial period, Korea-Japan trade largely consisted of Korean rice and Japanese cotton cloth. Most of the machine-made cotton cloth manufactured in Japan’s newly industrialized regions wound up in Korea. The rice exported from Joseon was intended as cheap provisions for the laborers in Japan’s factories.

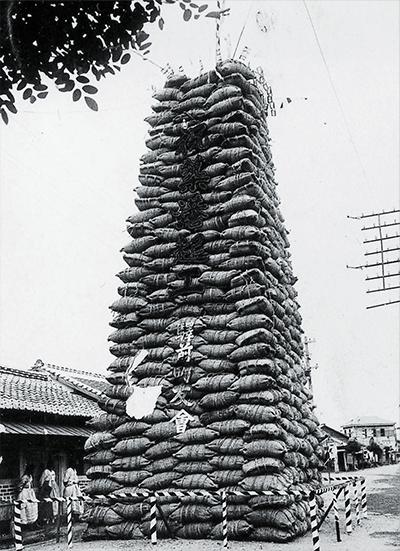

A tower of 800 sacks of rice marks the start of construction of the third port at Gunsan harbor in 1926. The project continued through 1933, resulting in three granaries capable of holding 250,000 sacks of rice. © Gunsan Modern History Museum

Rice Plunder

Under the trade structure, Korea degenerated into a food warehouse for Japan and a market for Japanese commercial goods. It meant chronic rice shortages in Korea, which dramatically raised the price of rice.

Having sold future rice during the spring lean season at unreasonably low prices, farmers found themselves with nothing to eat even when harvest time came around. As the price of goods increased, life became harder for farmers and merchants as well as the urban poor. The Donghak Peasant Uprising of 1894 began in Honam, or the Jeolla provinces, and spread around the country, instigated in part by Japan’s plunder of Korean rice and the economic ruin of farmers after the forced port openings. The protesting farmers demanded that foreign merchants be banned from trade and stopped from coming inland at will.

The Korean Empire opened Gunsan Port in 1899 with the hope of increasing customs revenues. Gunsan had a government granary during the Joseon period and the port served as the shipping center for Honam-grown grain as the government pursued industrialization in order to achieve economic prosperity and build a strong military.

With the opening of ports, commission agents and trading companies thrived in Gunsan. The government granted a special license to the commission agents and other merchants. They paid taxes to the imperial household in return for operating concessions that enabled them to develop into modern trading companies. Thus, the agents and merchants became sources for the government coffers.

After the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, however, when Japan’s ambitions in Korea and the plunder of the country became more blatant, the Korean Empire suspended its modernization efforts. When Japan established its residency-general in Korea in 1905, Japanese people began to enter the country in large numbers. The commission agents and other merchants of Gunsan formed cooperatives or companies to defend themselves against Japanese merchants but could not match their financial strength. After Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910, the Japanese government-general took over trade agencies and banned Korean trading companies in Gunsan.

The land around Gunsan and the Geum, Mangyeong and Dongjin river basins was then turned over to Japanese landowners. The rice they cultivated converged on Gunsan for shipment to Japan. In 1914, the port accounted for 40.2 percent of Korea’s rice exports, followed by Busan with 33.5 percent and Incheon with 14.7 percent, according to statistics of the Japanese government-general.

At one point in time, 80 percent of all land in the Gunsan area was owned by Japanese people. The many Japanese-owned farms were funded by big capital from companies such as Fujimoto, Okura and Mitsubishi. Their objective was to make profits, while Korean sharecroppers did the work.

On the other hand, Gunsan became a symbol of modernization. In the early years, a modern transportation network was constructed to speed up rice shipments to Japan. Korea’s first asphalt road appeared in 1908 between Jeonju and Gunsan, and in 1912, a railroad linked Iksan and Gunsan Port. This railway line had stations at every major Japanese-owned farm before reaching Gunsan, which had a floating pier to accommodate the high tides of the Korean western coast. Near the port, mills polished the rice to satisfy Japanese palates, and breweries also appeared.

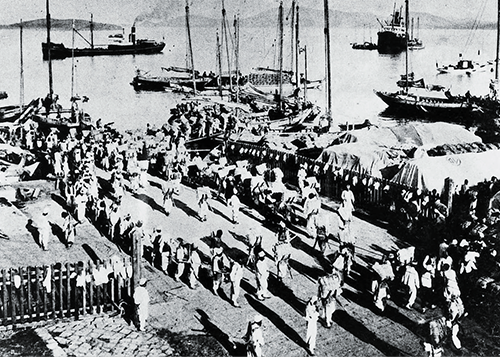

Workers carry rice at Gunsan harbor in this photo from the 1910s. Japan exploited Korean workers and plundered rice through the sharecropping system. Gunsan Port, opened in 1899, served as the main shipping port of rice grown in the fertile Honam region.© Gunsan Modern History Museum

In the old city center of Gunsan, where some 10,000 Japanese lived during the colonial period, more than 100 Japanese-style houses from that time remain. Many of those houses have been turned into cafés or tourist accommodations. They are popular as movie locations. © yeomirang

Traces of Modernization

Gunsan still retains many traces of its development under Japanese rule, rendering the entire city a kind of modern history museum. Among the remaining structures are the luxurious houses once owned by Japanese people, the Japanese Dongguk Temple, and the buildings that housed the Bank of Chosen (Korea) and the Eighteenth Bank operated by Japan. During the colonial period, a film theater with tatami mats opened, and plays were also staged there. The famous Lee Sung Dang Bakery, where customers form long queues every day these days, opened shortly after liberation in 1945 by purchasing the building and machines left behind by the Japanese family who had operated a bakery named Izumoya since the early 1910s. The bakery’s signature red bean paste bun is said to have been influenced by a similar Japanese sweet roll.