During the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), the Great Kyonghung Road was the only road connecting Seoul and the northeastern border area of Hamgyong Province in present-day North Korea. Little is left of the road today, but it continues to evoke emotions and memories.

A hillside neighborhood of multi-family residences is seen from Dream Forest, the fourth-largest park in Seoul. North Korean soldiers crossed the foot of Mt. Opae, where the park is now located, as they retreated during the Korean War.

“Kingdom,” a Korean zombie series produced by Netflix, transports world audiences to the 17th century Joseon Dynasty. The bloodiest battle in the show’s second season, released this year, occurs at Mungyeong Saejae (“Bird Pass of Mungyeong”), a steep mountain pass on the Great Yeongnam Road, which served as a defense stronghold and conduit of cultural intercourse during Joseon. In April 1592, however, a Joseon commander put too much faith in his 8,000 cavalrymen and set up camp on the plains below the pass. This allowed Japanese invaders to cross the pass unchallenged. King Seonjo immediately recognized the tactical miscalculation. Realizing that he was in grave danger, the king fled his palace early the next morning. Within the next three days, the Japanese forces seized the royal capital Hanyang, which is today’s Seoul.

It seems that the writer of the popular series, Kim Eun-hee, took this painful memory of the storied mountain pass as the catalyst for historical imagination: the survivors in “Kingdom” strive desperately to keep legions of zombies from getting any closer to the capital city. On the other hand, history buffs might compare the valiant defense to the South’s last stand against Northern troops bearing down on Seoul 358 years later. The crucial byway in this modern war was the ancient Great Kyonghung Road.

Seen from the Chinese province of Jilin, a bridge over the Tumen River connects North Korea and Russia. This bridge is crossed when traveling by train from the Rason [Rajin-Sonbong] Special Economic Zone in North Korea to Khasan in Russia. © Yonhap News Agency

Ruins of a train chassis and a North Korean freight car bombed by UN forces are displayed on the grounds of Woljeong-ri Station, a major tourist attraction near the Southern Limit Line of the Demilitarized Zone dividing the two Koreas. The railway station in Cheorwon County, Gangwon Province, has been out of operation since the division. © Yonhap News Agency

Lost Road

Castles are major landmarks in period dramas set in Europe. Their Korean counterparts are roads. Rough mountain roads and the act of passing through their gateways have been symbolic of hardship or changes in national fortune. Mungyeong Saejae’s historical significance is further enhanced by its riveting natural landscape. But while some of these roads are memorialized today as historic and scenic spots, others have been all but forgotten. This trip takes us on roads that don’t even have signs, let alone well-tended parks or memorial halls with explanatory plaques.

During Joseon, anyone traveling overland from the nation’s northeastern border to Seoul would have used the Great Kyonghung Road. It spanned more than 500 kilometers, much of it hugging the eastern seacoast. Today, the section of the road that lies in South Korea is treated as a historic national road. The designation ends at the Demilitarized Zone that separates the two Koreas. Surely, many Koreans who traveled this road to flee the North before or during the Korean War (1950-53) have never had a chance to return. It thus symbolizes someone’s wishes to go back to his hometown, another’s desire to find her lost self, or yet others’ hopes to simply return to something.

Starting from the northeast and going southward, the road tells a story of courage and heroics. In his geography book Taengniji (“Ecological Guide to Korea”), Yi Jung-hwan, a late Joseon silhak (“practical learning”) scholar, described inhabitants of the Hamgyong region as “strong and fierce,” a trait achieved by living in an area that “borders a land of barbarians.”

During the Japanese Invasions (1592-1598), Jeong Mun-bu, a low-level civil official, famously gathered 3,000 civilian warriors and successfully repulsed some 28,000-strong enemy troops along this road. Later, King Sukjong (r. 1674-1720) erected a monument in the town of Kilju to honor their victory. But during the Russo-Japanese War, a Japanese general sent it to the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo. Heeding a years-long campaign by the Koreans, Japan returned the monument in 2005, a century after it was stolen. The following year, it was sent back to its rightful place in North Korea.

The Tumen River constitutes the northeastern border of the Korean peninsula. Across the river lies the Russian border town of Khasan, so near that it seems within earshot of a spattering of Russian. A small bay with several lagoons occupies the downstream part of the river. South of the bay is the Rason [Rajin-Sonbong] Special Economic Zone, the first free trade zone in North Korea, and to the east is the site of Sosura Harbor. Google Maps shows no traces of this ancient harbor now. During Joseon, it was the site of the first signal fire post to warn of an enemy attack.

The Great Kyonghung Road started at Sosura, passed through Kyonghung (a.k.a. Gyeongheung, or today’s Undok), and followed the Tumen River upstream for a spell. It then squeezed through majestic mountains like a thin capillary before turning southward and crossing over Chollyong in Gangwon Province. Chollyong is a winding mountain pass. Exploiting the local topography, both the Joseon and the preceding Goryeo dynasties maintained a fort on this pass to serve as a stronghold for defense of the northeastern region. The part of Hamgyong Province north of this fort was called Gwanbuk, literally “north of the mountain pass,” and the area to the west was called Gwanseo, meaning “west of the mountain pass.” Past Chollyong, the road leads to the famed Mt. Kumgang (a.k.a. Mt. Geumgang), or the Diamond Mountains, in the southeast.

Beyond this point, it is difficult to discern any roads on Google Maps. This is an indication that the Demilitarized Zone is near. South of the DMZ, the road crosses the Gimhwa Plains to Pocheon and over the Chukseong Pass to Uijeongbu city. It is here that, suddenly, the three magnificent peaks of Mt. Bukhan appear before your eyes on the northern periphery of Seoul. The subway trip from here to the middle of the city takes about 40 minutes.

Monument and statues erected in honor of the soldiers who participated in the Battle of Chukseong Pass in Uijeongbu during the Korean War.

Departure from Seoul

The official departure point for the Great Kyonghung Road was Dongdaemun, the main east gate of the old city of Hanyang. However, it seems Jurchen envoys preferred Hyehwamun in the north, one of the city’s four minor gates. Hyehwa means “to edify by grace” and is thought to have referred to educating the Jurchens (ancestors of the Manchu people). To travel northward from Hyehwamun to Uijeongbu, it was necessary to cross Donam-dong Hill between Mt. Bukhan and the adjoining Mt. Gaeun. The original name of the hill was Doeneomi, meaning the “hill crossed by doenom.” Doenom was a derogatory term for immigrants from the northeast. At a certain point of time, the Jurchens became the main users of the hill road, thanks to Yi Seong-gye, later King Taejo (r. 1392-1398), founder of Joseon.

Yi’s father played a pivotal role in reclaiming the northeast, which had been ruled by China’s Yuan Dynasty for about a century during late Goryeo. Yi inherited his father’s power and position, and shielded the region from constant aggression. His amicable relationship with the Jurchens was a diplomatic asset that was useful to him as he founded Joseon. When the so-called Red Turban rebels invaded, Yi led his forces on the Great Kyonghung Road to protect the Goryeo-era capital of Gaegyeong, which is today’s Kaesong in North Korea. In his later years, after he stepped down from the throne, Yi spent the rest of his life traveling back and forth along this road.

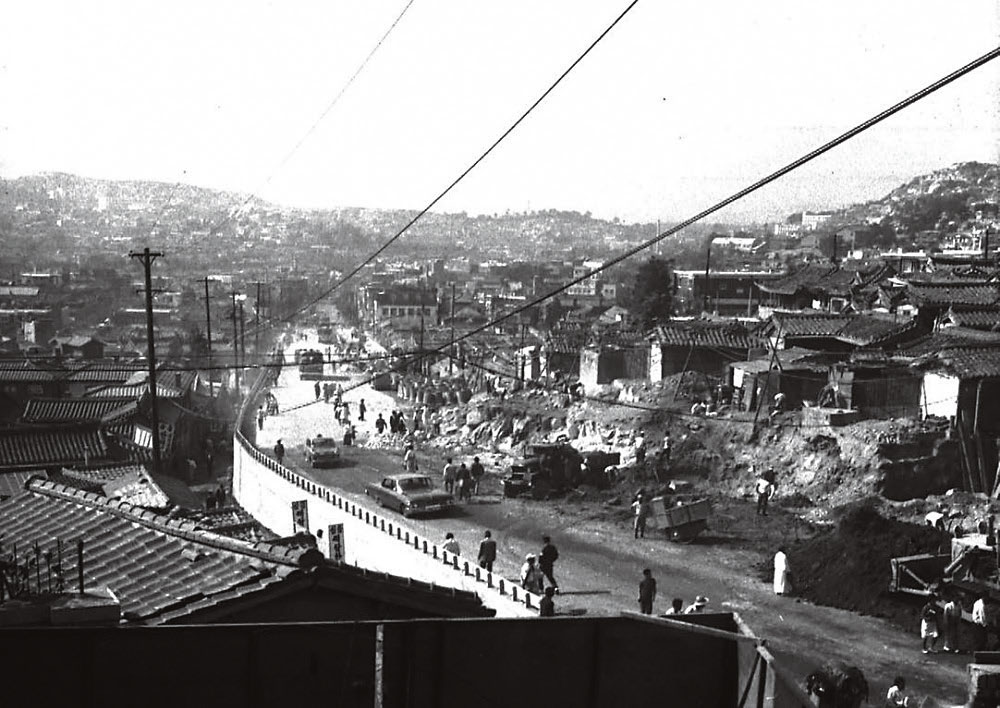

Miari Hill undergoes an expansion in this photo dated 1964. At the time, there was no walkway alongside the road so pedestrians had to dodge vehicles. © Seoul Metropolitan Government

Miari Hill today is a busy traffic thoroughfare connecting the old city center of Seoul and its northeastern outskirts. In June 1950, North Korean troops crossed this hill as they advanced on Seoul.

Hill of Sorrow

Donam-dong Hill was also called Miari Hill because a neighborhood named Miari lay beyond it. Today, Donam-dong is part of Seongbuk District, in the mid-north section of Seoul. Before the post-Korean War urban sprawl, the area was located on the outskirts of the capital. It was a major battlefront in the defense of Seoul during the Korean War. South Korean soldiers, who had been driven back by the advancing First Corps of the North’s Korean People’s Army in the Battle of Uijeongbu, fought to the last on Mt. Gaeun as they tried to stop the North’s tanks from advancing.

The defense line collapsed in the early hours of June 28, 1950, three days after the invasion began. By then, unbeknownst to the South Korean units on Miari Hill, North Korean tanks had already reached downtown Seoul. The battle stripped the mountain of its trees; now, long after the smoke of guns has been forgotten, an apartment complex commanding sprawling views stands on the spot.

Months later, after the tide of war changed, UN forces used the Great Kyonghung Road to pursue the retreating North Korean army, piercing deep into the northeast to the major industrial port of Chongjin, now the provincial capital of North Hamgyong.

In 1956, three years after guns had been laid down by an armistice agreement, the song “Miari, Hill of Wrenching Sadness” became a hit (see page 7). However, local residents preferred Donam-dong Hill to the sorrow-ridden name Miari Hill. Indeed, “Miari” cannot be detected anywhere today in the local government’s project to restore the old roads and create a cultural exploration trail.

It seems everyone living here is uncomfortable with the image of their home as the site of national tragedy, immortalized by a line in the song: “You−dragged away with hands tied up tight with barbed wire.” Moreover, nobody knows for sure whether the person who was dragged away was a rightist captured and killed by the retreating Northern troops or someone who had trusted the South Korean government and remained in Seoul only to be executed on charges of siding with the enemy. After the city was reclaimed, some 50,000 people were arrested on such charges and around 160 were executed.

Sites to Visit in Miari

1. Sang Sang Tok Tok Gallery

2. Miari Arts Theater

3. Miari Fourunetellers' Village

4. Hyehwa Gate

The defense line collapsed in the early hours of June 28, 1950, three days after the invasion began. The battle stripped the mountain of its trees; now, long after the smoke of guns has been forgotten, an apartment complex commanding sprawling views stands on the spot.

Dream Forest opened in 2009 on the site of a former amusement park. It has a 50-meter-high observatory.

Jeil Market in Donam-dong was opened in 1952 and renovated in the 1970s. Though not large, the traditional market has many old stores. It is a part of everyday life for the local residents, as well as a tourist attraction.

Distant Memories

National Road No. 3 runs northward from Mia Junction, over Suyuri Hill and along Jungnyang Stream to Uijeongbu. Taking into account that the road has been widened and moved several times over the past decades, it can be surmised that it roughly follows the same route as the old Great Kyonghung Road. Part of the original road actually remains, one block to the left of Banghak Junction. Amazingly, this stretch of road, which is more than 500 years old, still functions today, not as a historic site but as a part of everyday life. Some 10 meters wide and running 3 kilometers to Mt. Dobong Station, the road is lined with shops or traditional-style markets, with North Seoul Middle School located near its midway point. Residents go about the business of day-to-day life, sweeping their yards and buying and selling goods. They apparently have little interest in the joys, clamors and marvels that the road has witnessed over time. Hints of history are occasionally seen on roadside signs bearing detailed directions to the Mt. Dobong walking trail or the tombs of Joseon royal family members and other powerful men.

In the past, Miari Hill was like a gateway to Seoul. Without crossing the hill, it was difficult to buy anything of value or enjoy sights worth seeing. When eaten at the market in Donam-dong, even the most common rice and soup dishes cooked with potatoes or ox blood tasted cleaner and better. This was because Donam-dong was the last stop on the tram line, the urban terminus. Beyond was the countryside. The tram line opened in 1939 and operated until 1968, creating the area’s signature impression. But when Miari was designated for new town development in 2002 as part of a plan to achieve more balanced growth in Seoul, its history was shaken once again. The scale and speed of development was large and fast, and in less than a decade, people’s image of Miari was completely overturned. However, from the observatory in Dream Forest, one of the area’s symbolic spots, you can see the past and present of Seoul at the same time.

The road that runs north from Uijeongbu Station splits in two directions. The northeast road that forks off to the right is the Great Kyonghung Road, its first section passing the ceasefire line and running all the way up through North Korea to the Tumen River. I imagine a file of travelers: a vain, young nobleman on a sleepy mule that stumbles for a moment; young servants following behind with loads on their backs, oblivious to the blisters on their feet, with their destination still far away; and a young solider carrying a long rifle over his shoulder, bringing up the rear and bellowing a military song until his voice is hoarse. I stand there for a long while, just looking, unable to decide in which direction to go.