“The King’s Letters” is a film tracing the invention process of Hangeul in the 15th-century Joseon Dynasty. “Mal-Mo-E: The Secret Mission” sheds light on those who risked their lives to keep the Korean language and its letters from being vanquished under Japan’s colonial policy in the 20th century.

In “The King’s Letters” (2019), directed by Cho Chul-hyun, King Sejong is surprised to hear that Sanskrit can represent sounds. The film blended historical facts with cinematic imagination to depict how Hangeul was created.

I occasionally lecture for Korean students and was once embarrassed when one of them asked, “When were hiragana and katakana invented?” These syllabic components of the Japanese writing system evolved over a long period of time, so it’s hard to pin down the exact time of their creation. On the contrary, the origin of the Korean alphabet – who made it and when and why – is well documented. Or so I had thought before I saw the movie, “The King’s Letters” (2019), the debut work of director Jo Chul-hyun.

Unlike two earlier historical TV series with a similar focus, “The Great King, Sejong” (2008) and “Deep Rooted Tree” (2011), neither of which challenged the linguistic accolades universally bestowed on King Sejong, this movie leans in a different direction. The director exercised artistic license, with an intro stating, “This film is a cinematic adaptation of one of the various theories on the invention of Hunminjeongeum [the original name of Hangeul and literally the “correct sounds to instruct the people.”]

At the outset, King Sejong, played by Song Kang-ho (“Parasite” and “A Taxi Driver”), throws away volumes of books written in hanja, Chinese characters. “These are all useless scraps of paper,” he scoffs. “No matter how many books I publish, they are not delivered to the ordinary people.” The king wants everyone – not just those in elite circles – in his realm to be able to read and write. But he is under pressure; he’s losing his eyesight and his palace advisors oppose his ambitious goal, fearing it may upset China.

“Everyone knows how many pits are in a peach, but no one knows how many peaches are in a pit.”

Monk Shinmi explains the characteristics of Sanskrit to Prince Suyang and Prince Anpyeong, King Sejong’s second and third sons, respectively. In the film, the princes assist their father in his secret project to create Hangeul.

The King’s Present

Monk Shinmi (Park Hae-il), the kingdom’s leading phonology expert and keeper of the most complete collection of Buddhist texts, the Tripitaka Koreana, is secretly recruited to assist the king alongside a small group of other monks. Referring to ancient languages such as Sanskrit, Shinmi, who does not appear in any recorded history about the invention of the Korean , leads the effort to create vowels and consonants tailored to the Korean language.

Having Buddhist monks assist in the king’s project only adds to the conflict in court. The Joseon Dynasty was rooted in Confucianism and was officially anti-Buddhist. The king must therefore carry out the project furtively to avoid a full-blown confrontation with Confucian scholar-officials. And yet, an ideological clash inevitably erupts between the king and the monk, who is proud and outspoken.

No less impressive is the role of Queen Soheon, played by Jeon Mi-seon, who died days after a press conference to promote the film. As the Korean proverb goes, “When the hen crows, the house goes to ruin,” Korean women at the time were taught as girls to obey men, and having opinions was considered immodest. However, the queen says, “I believe the crowing hen brings prosperity to the family and to the nation,” asserting that women should be educated and empowered. As indicated by a scene in which the queen teaches her maids-in-waiting, the new alphabet was a means to empower those in the lower social strata.

In the end, palace officials adamantly oppose the proclamation of the new because of the involvement of the Buddhist monk. However, King Sejong is steadfast and releases the , telling his opponents to support his purpose. And of course, the book explaining the alphabet becomes the seed for eliminating illiteracy.

“Everyone knows how many pits are in a peach, but no one knows how many peaches are in a pit,” says Shinmi.

“MAL-MO-E: The Secret Mission” (2019), directed by Eom Yu-na, portrays the efforts of those who strived to publish a Korean language dictionary, risking their personal security under Japanese rule. Ryu Jeong-hwan (right), president of the Korean Language Society, and his clerk Kim Pan-su crisscross the country to collect local dialects. Ryu is based on a real person, while Kim is a fictional character invented for the film.

© Lotte Entertainment Co., Ltd.

Worth Risking Lives

“Mal-Mo-E: The Secret Mission” (2019), director Eom Yu-na’s debut film, is based on historical events of the late 1930s and 1940s, when scholars and members of the Korean Language Society risked their lives to secretly produce a Korean dictionary. By that time, Japanese imperialists ruling Korea had “demoted” and then outright banned the Korean language in favor of Japanese.

“Mal-Mo-E” is the title of the first Korean language dictionary, which began to be compiled in 1911 by Korean linguist and independence activist Ju Si-gyeong (1876-1914) and his students. The dictionary failed to be published because the authors either died or went into exile. The original manu changed hands several times until it was obtained by the Korean Language Society, which set out to edit and supplement the word entries. The dictionary was finally ready for publication in 1942, but scores of the society’s members were imprisoned and tortured before it could be printed. The manu, however, was not seized. It remained unseen until it was recovered in a warehouse of Seoul Station in 1945, immediately after the country’s liberation.

Protagonist Kim Pan-su (Yoo Hae-jin) is an illiterate ex-convict who survives by pickpocketing. This serves to highlight the fact that literacy was not guaranteed among all Koreans in the way King Sejong had intended. But Kim is a fictional character employed to show how delightful it is to learn to read and write.

Kim’s foil is Ryu Jeong-hwan (Yoon Kye-sang), president of the Korean Language Society. The two men cross paths when Kim attempts to steal Ryu’s briefcase, which contains a draft of the dictionary. A teacher (Kim Hong-fa) who was jailed with the petty thief vouches for him so that he is hired by the language society. This is how the streetwise Kim and the clumsy academic Ryu end up surreptitiously traveling the country together, collecting heritage words from dialects in many areas.

Kim finds it hard to understand how a mere dictionary is worth risking one’s life. Society member Gu Ja-yeong (Kim Sun-young) tells him, “Language, both spoken and written, is a container that holds national spirit.” She also interprets community spirit as reflected in the word “we,” pointing out that where Westerners would say “my country,” “my daughter,” or “my family,” Koreans say “our country,” “our daughter,” or “our family.”

“Mal-Mo-E” touched a patriotic nerve. It premiered shortly before the 100th anniversary of the March First Movement, a massive public rally which led to nationwide struggles by Koreans to regain independence. Although the basic plotline is familiar, the film’s alchemy of drama, comedy and historical facts filled theater seats, and the movie was included in the Korean film festival in Florence, Italy the following year.

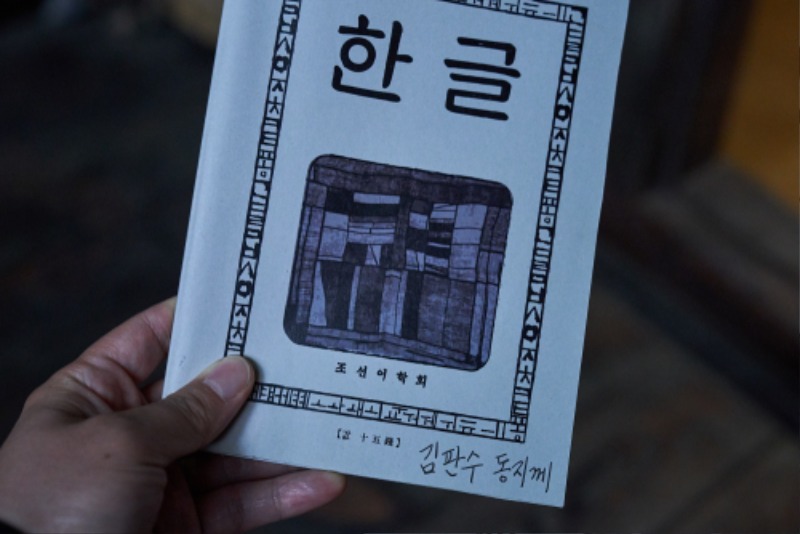

Kim Pan-su, who learned belatedly to read and write, finds his name written on the cover of “Hangeul,” a magazine published by the Korean Language Society.

© Lotte Entertainment Co., Ltd.