Bora Chung is a fiction writer who uses the surreal to depict the anxiety and fear lurking beneath the surface of everyday life. Her fast-paced narratives are not only gripping but also help console readers. After returning from the Berlin International Literature Festival, she shared her motivation and perspectives.

(Clockwise from top left) Midnight Timetable, a new novel collection published in 2023 by Purplerain, a brand specializing in genre literature of Galmaenamu; revised Korean edition of Cursed Bunny released in 2023 by Influential Inc. through its imprint Rabbit Hole; U.S. edition of Cursed Bunny released by Algonquin Books in 2022; Korean novel About Pain published by Dasan Books in 2023; English edition of Cursed Bunny published in 2021 by Honford Star in the U.K.

ⓒ Galmaenamu

ⓒ Influential Inc.

ⓒ Algonquin Books

ⓒ Dasan Books

ⓒ Honford Star Ltd.

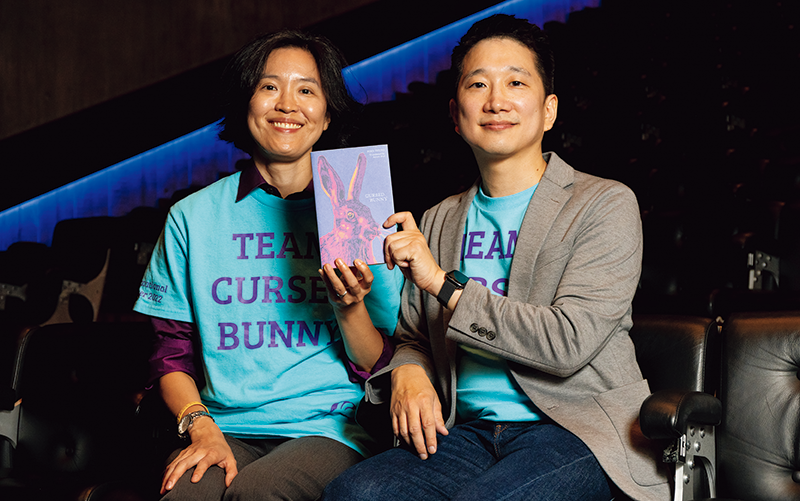

Bora Chung and her translator Anton Hur wear T-shirts bearing the title of Chung’s acclaimed novel at the International Booker Prize Shortlist Readings held at the Southbank Centre’s Queen Elizabeth Hall in London in May 2022.

In 2022, the English translation of Bora Chung’s short story anthology

Cursed Bunny (

Jeoju tokki) was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize, one of the world’s most prestigious literary awards. Last year, the U.S. edition was also named a finalist for the National Book Award for Translated Literature. The collection of ten works was praised for offering a chilling portrayal of the underlying fears and pressures of everyday life through a unique blend of horror, fantasy, and science fiction. Five years after its initial release, the book eventually became a bestseller in South Korea, creating quite a stir.

Born in Seoul in 1976, Chung grew up watching

Korean Ghost Stories, (aka

Hometown Legends; Jeonseorui Gohyang), a popular 1977–1989 TV series, and was exposed to her grandmother’s love for detective novels. After graduating from Yonsei University, Chung went to the United States to earn a master’s degree in Russian and East European Studies from Yale University, followed by a Ph.D. from Indiana University, where she wrote her dissertation on Russian and Polish literature.After returning from the U.S., she took up writing while teaching at a university, and had several novels and short story anthologies published. Over the years, Chung has also translated a number of Russian and Polish literary works, but after recently retiring from teaching, she now devotes all of her time to writing.

I met with the author at a coffee shop in Seoul’s Hongdae area, a beehive of university students. She had just returned from the Berlin International Literature Festival where she had participated in discussions with fellow writers.

What was the reaction to you being shortlisted for the International Booker Prize?

Readers from around the world started to share their thoughts with me directly through social media. For example, some readers told me they were too scared to go to the bathroom after reading my story “The Head” (“Meori”) because of the scene in which a head pops out of a toilet bowl. Other than that, I don’t feel that much has changed, except that I spend more time thinking about what to write.

How do readers view your stories’ fantasy elements?.

At this year’s Berlin International Literature Festival, I participated in two events; one on the topic of horror, and the other on magical realism. Both were panel discussions with other authors, and I had the opportunity to tell many ghost stories. Korean historical texts such as History of the Three Kingdoms (Samguk sagi) and Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms (Samguk yusa), compiled in the 1 2th and 13th centuries, contain many accounts of unusual events and stories involving mythical creatures. It seems that people have always been fascinated by such stories. Not only do they capture our imagination, but I feel they also serve to broaden our horizons. I also had the opportunity to share ghost stories at events in Singapore and Malaysia, and the response was very enthusiastic. The audience was highly involved in the Q&A sessions, showing a keen interest in all things Korean and asking very pertinent questions.

What makes Korean fantasy unique?

While the themes and content of stories may vary from one country to another, people all around the world seem to share a particular interest in supernatural phenomena. In this sense, the only distinctive feature of Korean fantasy is the Korean setting. Otherwise, I don’t think readers would be able to relate to my works.

Does your childhood influence your work?

Yes, indeed.

Korean Ghost Stories was a TV series that featured paranormal events, including ghostly apparitions. It was quite intriguing, and I enjoyed watching it as a child. My latest novel,

The Fox (

Ho), published this spring, is about a man who falls under the spell of a nine-tailed fox—a mythical creature known as

Gumiho in Korea— just like in the TV series. That said, I think my story is different in that it offers a reinterpretation of the timeless legend in a contemporary setting.

As an activist writer, do you think that writing alone isn’t enough to change the world?

I certainly feel that way. Last year, I found out about my nomination for the International Booker Prize right after I had finished a protest against the war in Ukraine in front of the Russian Embassy in Seoul. I’m constantly trying to stay vigilant so as not to get stuck in my own head and become detached from reality. At the same time, I believe that one of the functions of literature is to comfort readers. At the risk of sounding overly ambitious, I hope that my works can evoke in my readers the widest possible range of complex emotions.

Do you still see yourself as a realist writer despite your use of fantasy?

One of the defining features of magical realism lies in its ability to portray strange scenarios in a strikingly realistic way. Whenever I write about people, I inevitably find myself having to deal with real-world issues. To me, the act of writing is a way of trying to make sense of things I don’t understand.

How has your experience with literary translation affected your writing?

Doing translation work for so many years has allowed me to learn a lot about writing fiction. To begin with, the process of translating different languages into Korean has helped me improve my writing skills in general. It has also made me think deeply about a number of aspects at the heart of fiction writing, from plot and character development to narrative perspective. I draw a lot of inspiration from early 20th century Slavic literature because all kinds of new writing were widely accepted at the time.

How would you like global readers to engage with your stories?

Without readers there would be no writers. That’s why I feel like a new writer every time I meet a new reader. I’m filled with infinite gratitude. Given that Cursed Bunny has been translated into many different languages, I hope that readers will put their trust in translators without worrying about how the translation might differ from the original work.

What kind of works are you planning to write in the future?

I don’t think I have any other choice but to keep pursuing utopia. I plan to continue writing about how we might be able to build a happier and safer society for everyone, while also taking action myself. I believe this is the most meaningful thing I can do. And of course, I also plan to continue writing ghost stories.

Originally released in South Korea in 2017, Bora Chung’s Cursed Bunny was translated into English by Anton Hur and published by Honford Star in 2021. The following year it was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize.

Although Bora Chung’s stories may seem odd and uncanny, they are rooted in the author’s anger at the social injustices she hears about daily.

Cho Yong-ho Culture Desk Reporter, UPI News

Heo Dong-wuk Photographer