Situated on the western coast of Korea, Seosan boasts a unique topography created by extreme tidal waves, a rich cultural heritage, and reminders of the area’s importance to the defense of the nation.

ⓒ Seosan City

In September 2021, a promotional video for Seosan from the Feel the Rhythm of Korea series showed farm vehicles racing across a broad expanse of mud. Titled “Mud Max,” the video is a parody of the desert chase in the 2015 film Mad Max: Fury Road, directed by George Miller. The video went viral and Seosan, the city on the northwestern end of South Chungcheong Province, and its iconic surroundings became a popular tourist destination.

Juxtaposed to Korea’s wealth of mountains and hills, the Seosan area is called Naepo (firth) for its large and small tidal gullies that extend far inland. They are the product of one of the most extreme tidal ranges in the world. Garorim Bay, which lies in northern Seosan, has an average tidal range of nearly five meters. The tide can rise up to a staggering height of eight meters.

BOUNTY OF SEAFOOD

Yudu Bridge connects Ung Island to the mainland. The 600-meter span disappears as the tide rises, making it a popular tourist destination. The bridge is scheduled for demolition in 2025 as part of an ecosystem restoration project.

The tidal range of Seosan’s coastal waters has been the source of abundant marine resources. In 2016, the semi-enclosed inner Garorim Bay was designated as Korea’s first Marine Species Protected Area, and the 25th Marine Protected Area overall, for its rich biodiversity and pristine waters; in 2019, the area was expanded to 92 square kilometers.

The place featured in the promotional video is the Ojiri Tidal Flats at Garorim Bay. When flooded at high tide, a variety of fish can be caught, including gizzard shad and rockfish; after the tide ebbs, the endless mud flats reveal the country’s largest cache of

Ecklonia cava, a type of brown algae commonly known as paddle weed. Clams and cockles can also be found there. Fall is the season for small octopus, which was documented in the

Geography Section of the Annals of King Sejong’s Reign (

Sejong sillok jiriji), published in 1454. When Pope Francis visited Korea in 2014, he was served a bowl of small octopus porridge. He liked it so much that he had two more helpings.

To watch fishers catch small octopus, head to Jungwangri to the south of the Ojiri Tidal Flats. They first look for air holes, made by octopi to breathe while submerged in the mud, and then dig them up. In the autumn, visitors can try their luck at Garorim Bay.

At Ung Island, between Ojiri and Jungwangri, the bridge connecting the island with the mainland 600 meters away appears and disappears as the tide ebbs and flows. This so-called “parting of the sea” occurs twice a day. However, a new bridge is scheduled for completion in 2025, so you had better hurry if you want to witness this.

DEFENSIVE BULWARK

Garorim Bay, which lies adjacent to Seosan, provides rich and varied marine resources to local residents.

The abundance of the sea became a source of envy and avarice on land. The vast plain between the mountains to the east and the sea yielded bumper crops, making Seosan a frequent target of marauding pirates.

Finally, in 1416, King Taejong (r. 1401-1418) decided to turn the Haemi region to the east of Mt. Dobi into a defensive bulwark. Seosan thus assumed the role of the country’s front defense line in addition to being one of its most important agricultural regions.

Protracted fortification efforts began and the army unit in charge of central Korea was relocated to Haemi. Haemieupseong, a walled town in the heart of Haemi, about 12 kilometers outside of Seosan, housed the military high command. Its location on flat ground contrasted with other Joseon Dynasty fortifications built on hills and mountains.

Haemieupseong is one of the best-preserved fortifications in the country. It contains relics related to the persecution of Catholics. To ward of enemies, thorny trifoliate orange trees were planted along the walls of the fortress, earning it the nickname Taengjaseong, or trifoliate orange fortress.

Although part of the imposing walled town was torn down for urban development, it is among the best-preserved fortifications in the country along with Gochangeupseong in North Jeolla Province and Naganeupseong in South Jeolla Province. The South Gate and sections of the wall have remained intact, but other buildings have been reconstructed.

The wall is five meters high and stretches approximately 1.8 kilometers. It has two sawtooth-like structures that jut out. They are called

chi (雉), after the Chinese character for pheasant, a bird known to hide in the bushes when sensing danger. The extensions served as platforms for early warning and tactical defense.

Inside the walled town, there is a pagoda tree estimated to be well over 300 years old. Surrounding it are the old provincial government office, a guest house where visiting government officials stayed, and a prison. All are reconstructions. Up a short hill to the left of the government office is Cheongheojeong, a pavilion that was rebuilt in 2011. It offers a panoramic view of the entire area. The pine forest nearby is the perfect place to take a leisurely stroll. Haemieupseong enabled the inland regions to enjoy extended peace. Celebrating this history, the 20th Seosan Haemieupseong Festival is scheduled for early October 2023, ending a four-year hiatus caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

CULTURAL HERITAGE

Seosan also boasts a rich cultural heritage that is in harmony with nature. Some of the most notable sites are Gaesim Temple, Ganwol Hermitage, and the Rock-carved Buddha Triad in Yonghyeon-ri.

Daeungjeon is the main hall of Gaesim Temple. Designated as Treasure No. 143, it is known for its outstanding architectural aesthetics. Simgeondang, the monks’ residence, which beautifully blends with the natural surroundings, is also worth visiting.

Built in 654 CE, toward the end of the Baekje Kingdom, Gaesim Temple is ensconced in a thick forest between Mt. Sangwang and Mt. Illak. Its history, spanning almost 1,400 years, and its aesthetic value make it one of the four major temples in South Chungcheong Province.

Every step of the journey to Gaesim Temple is a beautiful experience. The Sinchang Reservoir, which you can see before reaching the temple, is the region’s main source of irrigation. On autumn mornings, it is enveloped in an auspicious shroud of fog that creates a mysterious aura for visitors. From the Iljumun (one pillar gate) at the front entrance, a 500-meter forest path leads to the temple. At the end of the path is a log split in half to cross over a rectangular pond. Next to it is a stone post engraved with the word “

gyeongji,” which means “looking at your reflection in the water and examining your thoughts and reflecting on yourself.” This fits with the name of the temple, which means “opening your heart and washing away your worldly cares and desires.”

The temple’s unpretentious simplicity makes it stand out. The Wooden Seated Amitabha Buddha is one of the oldest wooden Buddha statues in Korea, and the Daeungjeon, the main hall, retains its original appearance.

Among the temple structures, the most striking is Simgeondang, the monks’ residence. It is believed to have been repaired around the same time as Daeungjeon, with the kitchen having been attached to the side at a later date. The pillars made of crooked logs are the most eye-catching feature of the building. Their natural shape has been preserved with minimal trimming. The pillars have also not been painted as was the custom, which allows hairline cracks to be visible, a testimony to their longevity. Blending harmoniously with the fall foliage, the residence adds an idyllic, cozy atmosphere to the temple’s dignified presence.

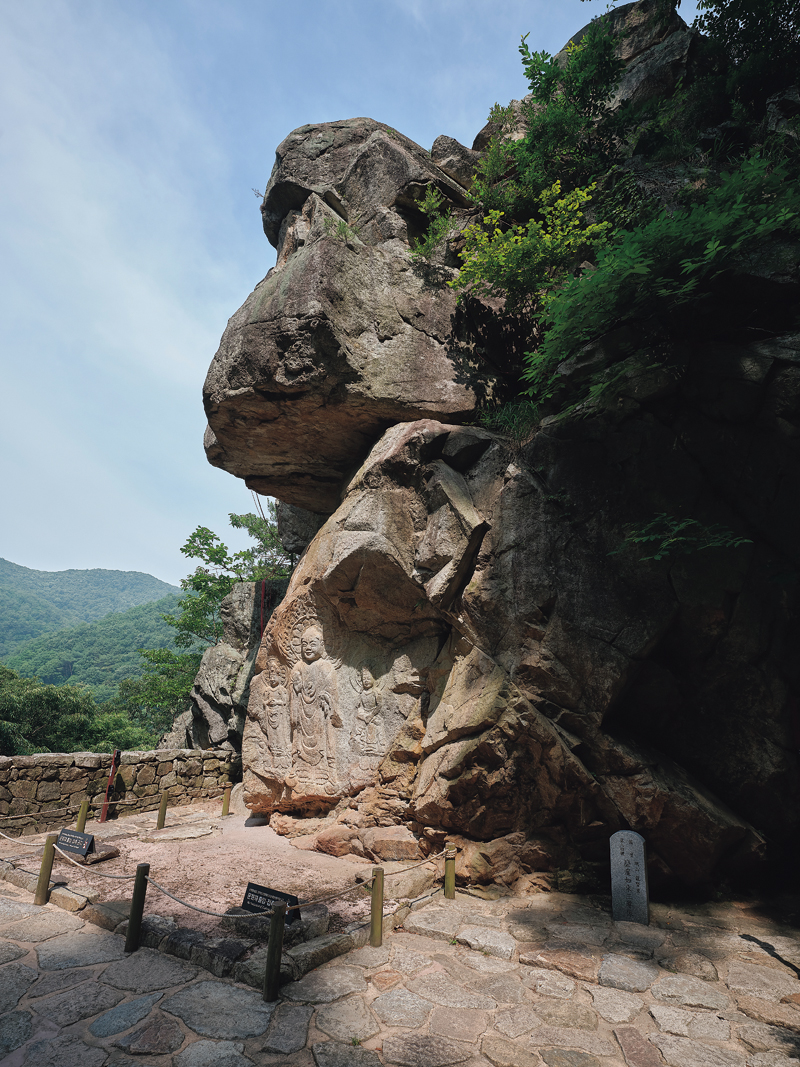

The Rock-carved Buddha Triad in Yonghyeon-ri, carved on a massive bedrock at the foot of Mt. Gaya opposite Gaesim Temple, is similarly simple and unadorned. It wears a playful, inviting expression. What is particularly captivating is the different aura it exudes during the day. Since the carving is deep and the facial features distinct, the angle of the sun alters its appearance. The rock carving remained hidden for 1,500 years; it was only discovered in 1959 and designated a national treasure in 1962. In reference to the ancient kingdom that once occupied the area, it became known as the “Smile of Baekje.”

The Rock-carved Buddha Triad was carved between the late 6th and early 7th centuries. Particularly captivating is the Buddha’s smile; it appears to change as sunlight hits the face at different angles.

Another must-visit place in Seosan is Ganwol Hermitage, which was also featured in the “Mud Max” video. It is located on Ganwol Island, Seosan’s southernmost island, in Cheonsu Bay. Like on Ung Island, when the tide ebbs twice a day, a 30-meter-wide path is exposed, allowing visitors to reach the island on foot. During high tide, a boat can be used instead. The island is called

yeonhwadae (lotus pedestal) because it resembles a lotus flower when the road disappears under water. Whether at low or high tide, it is beautiful and picturesque, and at sunset, the hermitage feels even more serene and peaceful.

INDOMITABLE SPIRIT

The Seosan A-Region Seawall to the east of Ganwol Hermitage is worthy of note. Building the seawall to reclaim dry land was a massive undertaking because the extreme tidal range of the area wreaked havoc on its construction. Even boulders the size of cars would be swept away by the strong currents, with speeds exceeding eight meters per second.

To close the last section of the wall, a 230,000- ton Swedish oil tanker, waiting to be scrapped in the Port of Ulsan, was sent on its last journey and deliberately sunk to block the troublesome tide. The rest of the construction was completed smoothly whenever the current was weak.

After 15 years and three months, the project was finally completed in 1995. The seawall stretches 7.7 kilometers, creating more than 10,000 hectares of reclaimed farmland. At the time, this was equivalent to one percent of Korea’s total agricultural land. This vast farming area yields enough rice to feed 500,000 people for about a year.

A trip to Seosan is not only a journey into its past, but an occasion to reflect on Korea today through its people who champion environmental sustainability while taking full advantage of the rich marine resources. Haemieupseong and the Buddhist cultural heritage exemplify the culture of valuing not just individual happiness but the well-being of the community as a whole. Finally, the area’s large-scale land reclamation is a testament to the dauntless spirit of the Korean people.

Kwon Ki-bong Writer

Lee Min-hee Photographer